Immune cells like to double up for stronger infection fighting power

Once thought to be experimental artifacts, these cell pairs could provide important insights into the immune system

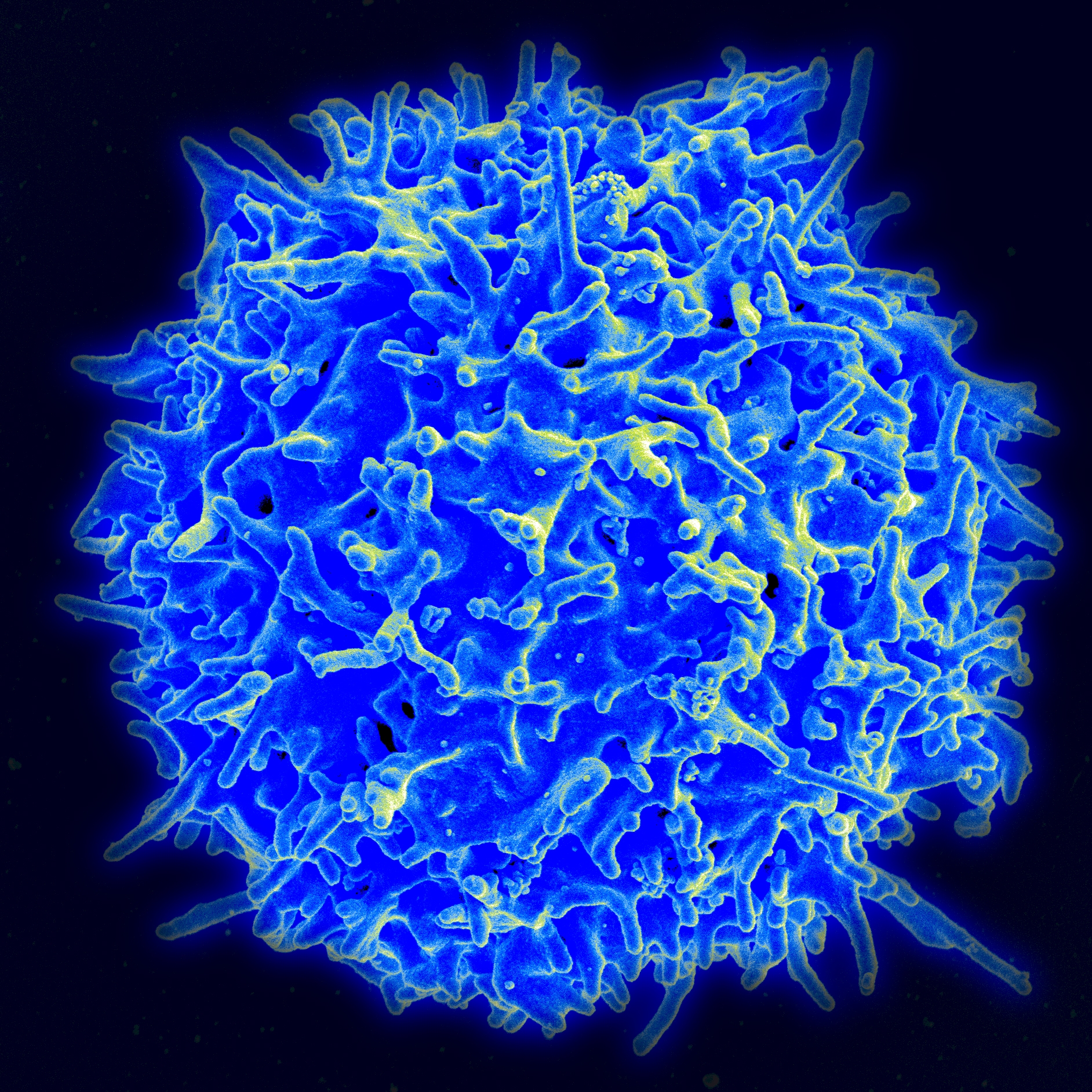

NIAID

Scientists have long known that physical interactions between different types of immune cells are essential for proper functioning of the immune system. Yet for years, doublets — or pairs of cells — were often discarded in some types of experiments because scientists thought they were simply a failure of the processes and machines used to separate different cell types in the lab. A new study has countered this longstanding assumption, showing that cell doublets are probably not just a result of faulty lab equipment and instead are a naturally-occurring component of the immune system.

NIAID

Bjoern Peters’ group at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California uses a technique called flow cytometry to study immune cells. Immune cells fight off infections and come in more than a dozen varieties. Studying all of them together would be difficult, so the researchers separate them based on certain tags the cells carry, like sorting mail. Flow cytometry allows scientists to feed in a hodgepodge of cells and come away with neat little groups sorted by their tags.

The sorted cells are usually pretty happy by themselves and don’t stick to other cells in the group. Every once in a while, though, pairs of cells called doublets turn up. For years, doublets were discarded as artifacts of the flow cytometry process.

Peters’ lab, however, became interested in these doublets that were observed in flow cytometry experiments when they identified a strange group of immune cells. Although at first the strange cells appeared to be just T-cells, they were actually doublets formed by two types of immune cells called T-cells and monocytes. After some more careful separation and analysis, the group found that levels of these doublets were associated with infections like tuberculosis and dengue. Doublets could also be affected by recent vaccinations.

The researchers now plan to see if more doublets like these exist and use them to further study how immune cells work.