Eating more fiber feeds whipworm parasites in our guts

New research shows that interactions between diet and parasites might make people with whipworm infection sicker

Has your doctor ever advised you to increase your fiber intake to improve your overall health? Well, if you've got a parasite, it turns out that is terrible advice! Researchers at University of Copenhagen have discovered that parasitic gut worms (in particular, Trichuris muris, a whipworm) survive and reproduce easier in mouse gut tracts that have higher levels of fermentable dietary fiber.

Trichuris muris is a mouse parasite that is used as a model to study human T. trichiura infections. T. trichiura is a roundworm humans can catch via ingestion of soil, like on our hands or food, that has been in contact with infected feces containing eggs or larvae. While these parasites can be a problem anywhere, they are most prevalent in warm or humid climates.

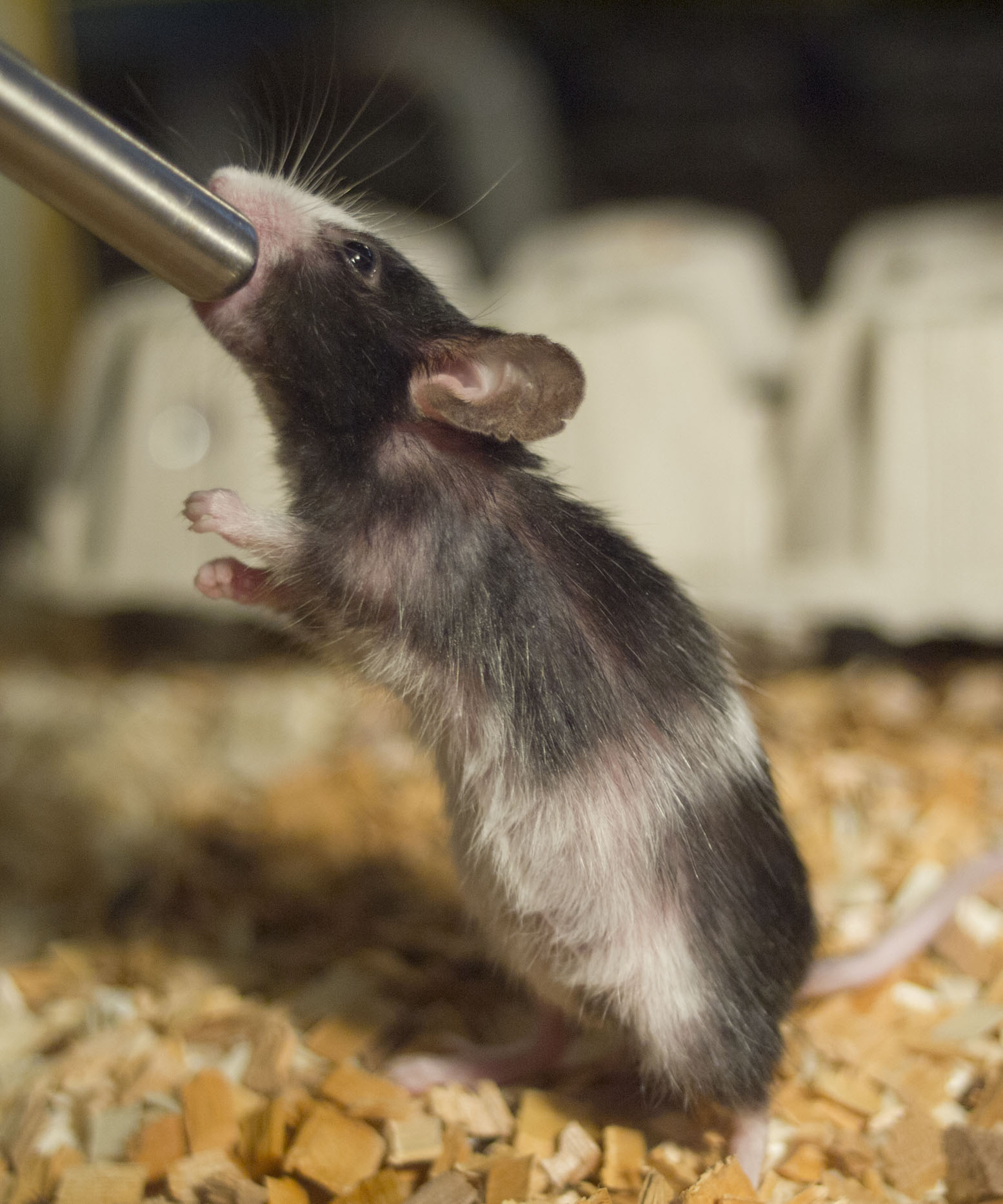

Reseachers fed mice inulin and T. muris eggs in their food to understand how they interacted in the gut

Tiia Monto [CC BY-SA 3.0]

These researchers were interested in the correlation between lack of dietary fiber and chronic intestinal inflammation. They decided in particular to study inulin, a soluble fiber derived from plants that is also a prebiotic. Prebiotics feed your "good" gut bacteria, stimulating their reproduction and ultimately leading to a healthy gut microbiome.

They fed mice a high or low dose of T. muris eggs in addition to inulin in varying doses in their food, and observed the result. They saw that some of the mice had showed an immune response related to gut inflammation (similar to symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in humans). Normally, these responses are good for eliminating bad bacteria or food contaminants. But in this case, the immune response did not eliminate the parasites. They actually stayed in mice guts up to 35 days post-infection! This is because inulin caused the growth of Proteobacteria, a gut bacteria that happens to be T. muris' favorite snack.

It turns out dietary inulin and high doses of T. muris parasites together caused severe inflammation and gut microbiome imbalance that made the perfect environment for parasitic persistence. This study points scientists toward studies on the interactions between inflammation, diet, and parasite load to help people affected with parasites.