Storytelling is the antidote to Americans' mistrust of science

Beyond just making us feel good and entertained, storytelling can effect change

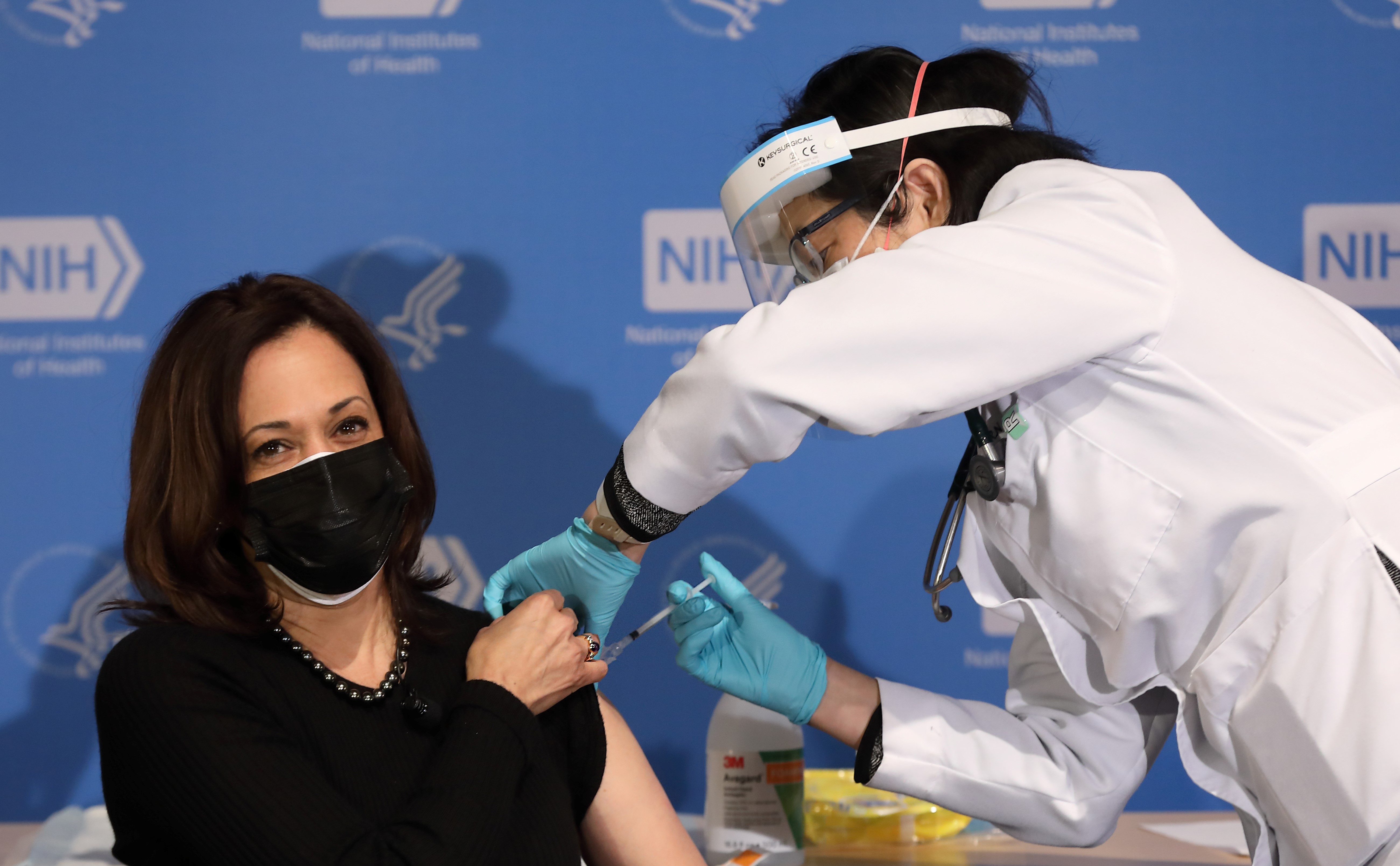

NIH/Chiachi Chang via Flickr.

With a collective exhale, we watched the Biden-Harris administration transition to power in January. We have a lot of work ahead to transform our unjust systems and address the defining crises of our time. For climate change and COVID-19, science will be critical for creating positive outcomes for people and planet Earth. But the United States just spent four years with the Trump administration downplaying and promoting distrust in science.

How do we move on from Trump’s post-truth era and build back trust in science? We do it with storytelling.

The 2020 Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Civic Life and Public Health Survey, which surveyed nearly 1,500 United States adults, revealed that trust in science was split almost evenly. Fifty-four percent reported trusting science “a lot”, while 46 percent reported trusting science “some”, “not much”, or “not at all”. Critically, the survey highlighted how trust supports mitigation efforts. It was trust in science – not political affiliation or other socioeconomic factors – that was most associated with people supporting social distancing.

In 2018, the Wellcome Global Monitor polled over 140,000 people across 140 countries in the Global North and Global South. Its findings identified levers that bolster trust in science. At the country level, income inequality mattered the most: in wealthy, low-inequality countries like Iceland and Norway, on average 30 percent of people had high trust in scientists. Conversely, in wealthy countries with high income inequality like the United States and Argentina, the average was only 19 percent. At the individual level, people with confidence in major institutions and opportunities to learn about science were more likely to view scientists as trustworthy.

Vice President of the United States Kamala Harris receives her second dose of the Moderna, Inc., COVID-19 vaccine, at NIH on January 26, 2021.

NIH Image Gallery via Flickr.

We can pull these levers – especially at the individual level – to build back trust in science. When we are immersed in a story, our brains release a neurochemical called oxytocin. As oxytocin flows, we experience feelings of connectedness, generosity, and empathy. It's no wonder oxytocin is nicknamed the "love hormone". And that emotional stimulation is what gets us lost in a good story. Without a doubt, our brains are naturally tuned toward good storytelling.

Our affinity for storytelling transforms how audiences comprehend messages. As a result, storytelling allows scientists to deliver complex information in engaging and understandable ways. It takes audiences on a journey using characters and the scientific process. In focusing on people and process, storytelling moves science beyond data and help audiences comprehend why the work is important.

And the impact of storytelling works in two directions. Stories not only affect how storytellers influence audiences, but also how audiences perceive storytellers. Audiences see storytellers as warmer and more competent when listening to stories – thanks in part to the oxytocin flowing in their brains. In short: stories garner trust. Moving forward, incorporating stories into science will build positive associations between scientists and trustworthiness.

Importantly, the movement toward incorporating stories into science must include diverse storytellers and experiences. A Pew Research Center survey showed that 21 percent of Black Americans had “not too much” or “no” confidence in scientists acting in the best interest of the public. Only 11 percent of White Americans and 12 percent of Hispanic Americans answered similarly.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study targeted poor Black men, and denied them adequate medical treatment.

CDC via Wikimedia Commons.

Black Americans are more skeptical about intentions of scientists – and justifiably so. Black Americans like Henrietta Lacks endured historic abuses in scientific research that undermined confidence in major institutions. It's a reminder that we are not only dismantling distrust from the last four years, but also from a longer racist history. As we engage in storytelling, passing the microphone to diverse storytellers will be critical for building trust in science. By holding witness to a range of experiences, we can build trust across communities that were historically excluded from the scientific process.

History tells us that, beyond just making us feel good and entertained, storytelling can effect change. The 1960s were a tumultuous and divisive time for the United States, marked by political assassinations, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War. Simultaneously, a pesticide called DDT was poisoning wildlife and contaminating our soil and drinking water. And in 1962, Rachel Carson exposed the adverse environmental impacts through storytelling with her book Silent Spring. Ultimately, her stories catalyzed federal regulations that still exist today. Silent Spring is a testament to the power of storytelling in science and its ability to bring about positive change – even in times of crisis.

We have a long road ahead to dismantle the distrust from Trump’s post-truth era and our long racist history. It will take time, energy, and empathy. But with the power of storytelling, we can begin to build back trust in science. Let's get started.

Peer Commentary

Feedback and follow-up from other members of our community

Francesco Zangari

Molecular Biology

University of Toronto

I think one of the most important but hardest things when starting in science communication is learning how to tell a good story. The data, while it may compel scientists, often does little to change the mind of someone who is distrusting of institutions. However, forming that connection through a story is something all humans can relate to.

I think one thing I’d add to this story is the role of acknowledging someone’s position and building a rapport as you tell a story. I’ve found in my personal interactions with the people around me who don’t trust institutions or are uneasy about medicine, appreciate your understanding of why they feel that way. Not that one should reinforce obvious falsities, but I think this with good storytelling is the recipe for repairing the distrust in science and our institutions.

Noah Yann Lee

Computational Biology

Yale University

Relating to the article’s recommendation of including diverse storytellers and experiences, I heard about “Reaching Out to Communities of Color on COVID-19 Vaccines” using cultural ambassadors who are leaders and members from the local community (NBC & Yale News).

Their mission is to regain trust in science initiatives by building a relationship with the community. Storytelling is a great tool for this, and I want to emphasize that this process of gaining trust is part of building a relationship over time. Extending this article into the framework of building a relationship opens up even more ideas from other approaches, like community outreach strategies or these Massive-Science-recommended communication resources.

Jayati Sharma

Genetics, Epidemiology

Johns Hopkins University

I would add that researchers should consider more deeply the real-life implications of their work and how it can improve lives – through policy, advocacy, organizing, etc. Conducting research that actively not only acknowledges, but addresses & works to remove disparities and inequities that plague people’s lives requires involving people in the scientific process, whether through storytelling, research participation, or even community consultancy. This kind of science, which directly relates to an average person’s life, is more conducive to storytelling, because the listener knows the actors. Using science to work with and not just for the people is a great way to instill and maintain their trust.

Brittany Kenyon-Flatt

Biological Anthropology

North Carolina State University

The statistics detailing how who tends to have confidence in science are always staggering, and I find it even more interesting when we divide them further (like, who agrees with/understands evolution, or who agrees with/understands physics). Like you point out, there are many ways to engage communities in our science, and in order to make real, meaningful contributions we need to creatively think about ways to engage different groups of people. In some ways, this starts with great, narrative books like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks or Hidden Figures, and luckily these books became popular enough to grasp a wide audience. Continuing to share these stories in new, creative ways will help to bridge to gap and increase the general confidence in science, and I’m hoping that sharing science outside of academic journals continues to become more popular and accessible.