Five facts about Pamela E. Harris, Mexican-American mathematician and educator of "leaders of character"

Just don't call her an underdog

SACNAS/Lisa Helfert

Pamela Harris works on the theorem of Zeckendorf. She explained it like this: if you have all the Fibonacci numbers (a special series of numbers, where, starting with 0 and 1, you add two in a row to make the third number) you can take any whole number, like 2020, and write it as a unique sum of non-consecutive Fibonacci numbers (if you start from 1 and 2). To be honest, she lost me there. But there’s a lot more to Harris than her research, which is why she's a science hero to me: she's an accomplished educator and a fierce advocate for immigrants. Her family also came to the US from Mexico, just like my mom's family. I sat down with Harris, an assistant professor at Williams College, during the 2019 SACNAS National Diversity in STEM conference, to learn more about her life and career.

Her family laid the foundation for her success

Harris is Mexican-American: her family emigrated from Mexico twice, first to California, then to Wisconsin when Harris was 12 years old. Harris grew up undocumented in the US, always nervous about her immigration status. Although she loved school, she was unable to apply to a four-year university without a Social Security number. But her parents encouraged her to get as much education as possible, so she enrolled in her local community college. Harris earned two associate's degrees in just two and a half years, all with a 4.0 GPA. She later married a US citizen, which changed her immigration status. She was excited to continue her education, and went on to earn a bachelor's degree and a PhD in mathematics.

Harris, like most of us in academia, has been told (both implicitly and explicitly) that you can only be a “good scientist” if you can dedicate all your time to work – an idea she rejects in favor of prioritizing her family. That’s in part because Harris is a mother – her daughter, Akira, was still a baby when Harris was starting graduate school. “Being a mathematician and professor has made me a better mother, and vice versa,” she said. “There’s no separation between my personal life and my professional life. That line is extremely blurry.”

She loves teaching

When I asked her about her favorite part of her job, Harris beamed and said, “I love my research, but the part I love the most is really seeing my students thrive.” She doesn't just love teaching – she’s really good at it, too; she won a national teaching award for young faculty in 2019. She goes above and beyond for her students, and tries to make sure they feel part of a community at Williams – even having them over for dinner. “The students wrote heartfelt letters [for my teaching award nomination], and mentioned things that I don’t think of as part of my job that I just do,” she said. It’s clear that Harris has a positive impact on her students both in and out of the classroom.

In case you’re wondering, the part of her job that she enjoys less is administrative tasks that she doesn’t feel passionate about, or as she put it, “things not as close to my heart.”

People are sometimes surprised that she is a mathematician

Harris is sometimes expected to be an expert on Mexican history and culture, even though she grew up in the US. “I am not an individual to them. I represent an entire group of people,” she said. Even worse, white mathematicians have been “surprised” to see her at conferences because she “doesn’t seem like a math person.” When those not-so-micro-aggressions occur, Harris told me that she always wants to ask her colleagues why they think that, and educate them about why it’s a hurtful thing to say. But “it’s more taxing to help people grow than to self-protect,” so she can’t do it every time.

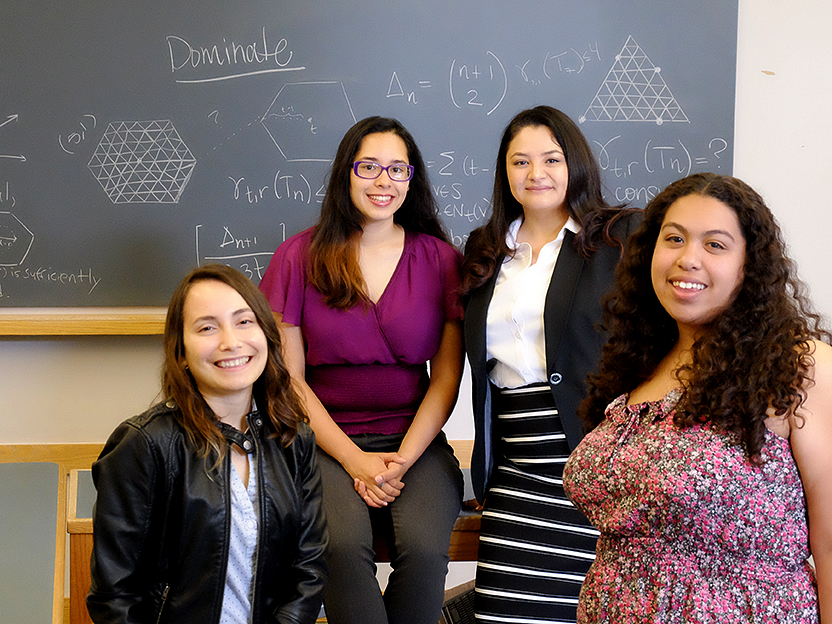

Harris and three students, all math majors at Williams

Shannon O'Brien

That's part of why she founded Lathisms, a project that features Latinx mathematicians during Hispanic Heritage Month. She and her co-founders want to showcase the contributions of mathematicians who look like her.

She said she loves going to diversity-focused conferences like SACNAS because she's surrounded by colleagues with a wide variety of backgrounds. “I don’t have to look around to see where I’m going to sit, and scour for someone who might be friendly and will strike up a conversation without being surprised that I’m there.”

She worked for the US Army

After earning her PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Harris ended up teaching mathematics at the US Military Academy (West Point) for four years. In addition to teaching math, part of her job was to “train leaders of character” for the US Army. She felt like she was serving the US, which she really enjoyed. “It taught me to be a better person,” she said. “We were encouraged to have conversations about being good leaders, and I was empowered to call out students on their crap.”

She doesn’t like to be called an underdog

When Harris shares her family’s story, she’s had people say that she’s an underdog. People see her history of immigration and her Mexican-American background as a hurdle to “overcome.” But she doesn't feel like she overcame hardships just because she "made it" into academia. One of her frustrations is how little immigration policy has changed since she came to the US. “It’s 20 years later and people are in cages at the border. We haven’t overcome systemic racism just because I got through the academic system,” she said.

Her background isn’t a hurdle, she told me. Instead, “My story is about community and the strength that gives me.”