Genetic engineering can save the American chestnut tree from a deadly fungus

If the USDA approves it, this would be the first use of genetic modification for conservation purposes

Timothy Van Vliet on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

One in four hardwood trees in the eastern United States was once an American chestnut. But no one today can take a walk in these woods beneath the once towering chestnut trees because the species is functionally extinct.

First spotted in the Bronx Zoo in 1904, Cryphonectria parasitica (commonly known as chestnut blight) is a fungus that parasitizes the American chestnut. Thought to have been brought to the United States from Asia, it grows on and beneath the bark, releasing an acid that kills the tree. The blight spread across the country at a rate of roughly 50 miles per year. It was spread, in part, by loggers carrying the fungus on their shoes and axes. Communities in Pennsylvania burned infected trees to no avail – by 1940 most adult American chestnut trees were dead.

The decimation of the chestnut is among the worst ecological disaster in the world’s forests in history. But now, genetic engineering and conservation are being brought together to save a species, for the first time.

The American chestnut was integral to life in the eastern US. Chestnuts were a source of food and medicines for the Cherokee, and were culturally important to the Iroquois. When white settlers expelled Indigenous peoples and occupied the land, they relied on the tree for food, lumber and often their livelihoods. Its lumber was remarkably useful for building. Described as a tree that “carried man cradle to grave in crib and coffin,” it was soft and easy to work while being rot-resistant. Tannic acid from the tree fueled 21 tanneries in the Appalachians. Chestnuts were used to feed livestock – for several months of the year, hogs would roam the woods, eating nuts that coated the forest floor. Many species that people hunted as game ate chestnuts as a dominant food source. The loss of the American chestnut threw ecosystems off balance and led to the extinction of at least seven moth species that called the trees home.

Using the naturally blight-resistant Chinese chestnut, the USDA started a program in 1922 to breed for blight resistance. Initially thought to be linked to one or two genes, resistance is now understood to be much more complicated, potentially involving nine of the 12 chestnut chromosomes. This complication makes the task of full-scale resistance via breeding daunting. Breeding can also lead to negative traits such as male sterility and traits that are phenotypically more Chinese chestnut than American chestnut.

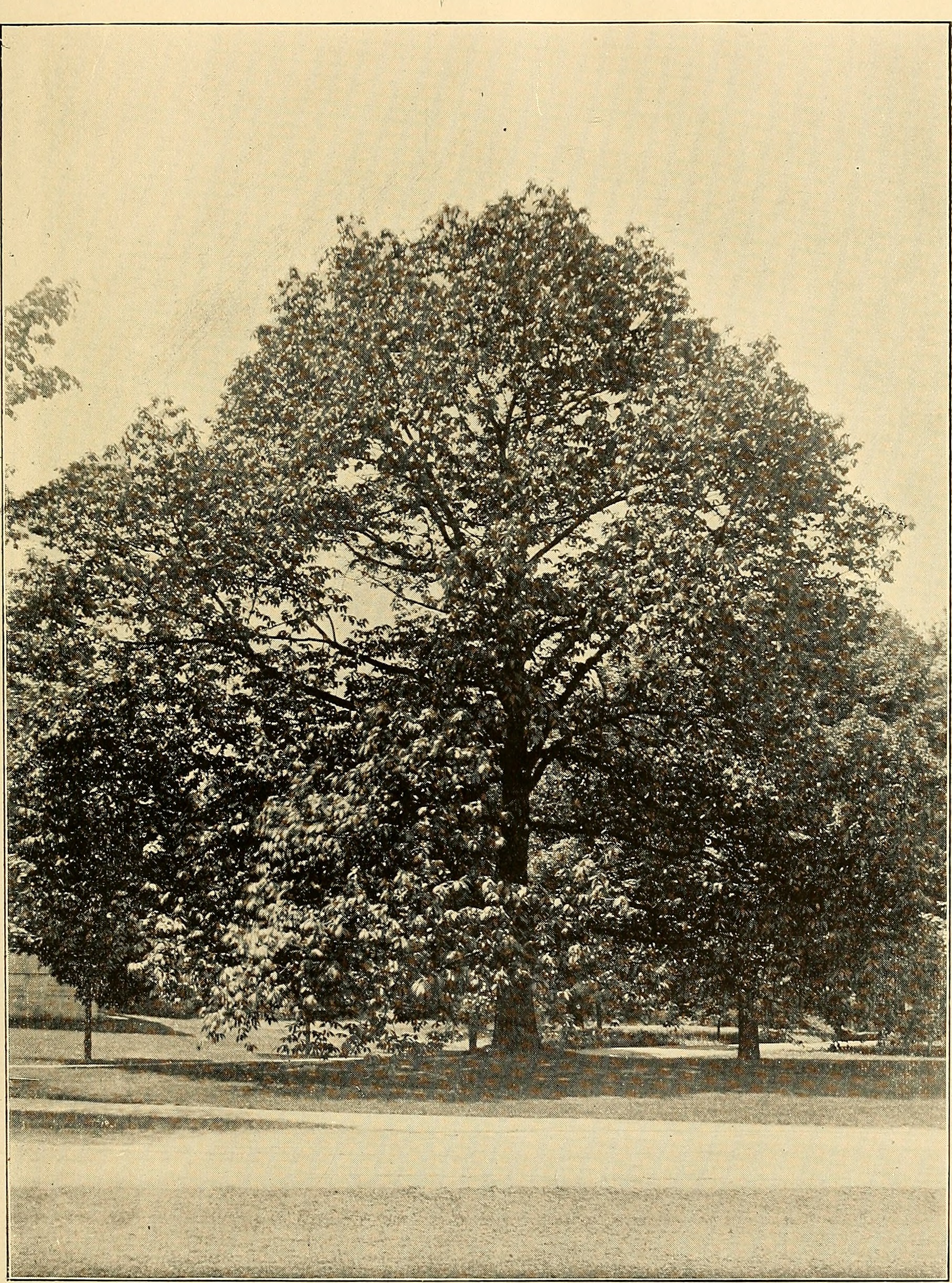

An American chestnut on the grounds of Vassar College, 1909

Via Wikimedia

The most promising strategy is also the simplest. In 1990, researchers at SUNY-ESF, the State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, started trying to make resistant American chestnuts not by breeding, but by genetic engineering.

With knowledge that the fungus damages trees by releasing oxalic acid, the scientists sought genes that could protect against this compound. After a few false starts, they ultimately landed on a gene from wheat encoding a protein that could break this acid into non-toxic parts. They were able to effectively get DNA into tree ovaries by using a bacterium as a conduit, and selecting for those with effective gene transfer. The first genetically engineered trees were planted in a field trial in 2006.

The trees proved remarkably resistant. The single gene addition has shown blight resistance similar to that of the Chinese chestnut. Importantly, the gene is passed down to offspring, ensuring resistance will not be lost and making this a viable strategy for use in the wild. These researchers, along with the American Chestnut Foundation, submitted a deregulation petition to the USDA in January 2020 to allow use of these trees at a much larger scale in the wild. A decision will probably be made sometime in 2021 or 2022.

Infection with chestnut blight has caused this tree's bark to split open

US Forest Service/USDA on Wikimedia Commons

If approved, the decision would be the first use of genetic engineering for the purpose of conservation, and has the potential to change eastern US forests if the chestnut tree is reintroduced in the wild at even a fraction of its former range. The proposition forces us to ask deep questions about what we are willing to use genetic engineering for. Some people are arguing against its approval due to lack of long-term studies of the modified tree's impact on the environment and the threat that approving planting of genetically modified chestnut trees could lead to easier approval for planting genetically engineered trees of other species.

While the issue of genetic engineering is polarizing in any context, use in the American chestnut is decidedly safe. Both the tree and the fungus have the unique claim of almost a century of study. The genetically engineered tree and unmodified American chestnuts have been shown to be functionally identical in key ways, including chestnut composition. Transfer of the gene to other species is extremely unlikely, but even if it were to occur, the transgenic gene is not unique – it is found in at least 30 different plants.

While genetic engineering is scary to some, it is widely used to produce medicines and has proven time and again to be a safe strategy for adapting foods to human needs. In fact, the addition of one gene is a much less intrusive genetic intervention than cross-breeding, which swaps large amounts of DNA between organisms.

Another important advantage is that the transgenic trees do not kill the blight, but allow them to live long term in a symbiotic relationship. This is important because outright killing of the fungus could apply pressure for the species to evolve, potentially undermining the efficacy of the intervention.

If the USDA approves the genetically modified tree, it will be the first case of using genetic engineering for conservation. This could set an important precedent in our Anthropocene-era world. By 2070, one-third of plant and animal species are projected to become extinct due to climate change alone.

What will we be willing to do to save them? Not all species will not have as much research into restoration behind them, and the stresses applied by climate change are different from that of an invasive fungus, but with our rapidly expanding scientific understanding of genomics and genetic engineering, the techniques used to create blight-resistant chestnut trees can eventually be applied to other plant species.

Using genetic engineering to bring back the American chestnut would not only save a functionally extinct species, but could open the door to saving many more.

Peer Commentary

Feedback and follow-up from other members of our community

Olivia Box

Natural Resources, Forest Ecology

University of Vermont

This is such a timely article given the current influx of invasive pests to the United States. Chestnut blight is an evergreen tale about the dangers of nonnative pests and pathogens. I appreciated the detail you provided about how breeding can lead to negative traits, and how it is a complicated process.

As someone without a strong background in genetics, I’m curious why you called it the “simplest method”?

Looking forward to following this story as a decision is made!

Margaret Swift

Ecology

Duke University

Great article, well done with covering the many different bases of research or interest concerning the chestnut. I think it’s especially important that you addressed the fears that follow genetic engineering, emphasizing that this decision would not be made lightly and that there is a century of research to back it up. As scientists, sometimes we can discount the public’s fears of things like genetic engineering as “uneducated” or worse, but if we truly believe it’s for the best in a situation, it is our job to address these fears head-on, honestly, and without condescension. Bravo on hitting those three marks.

I also really liked the point about the GMO trees not killing the blight outright; this is something I hadn’t considered but seems like a unique opportunity to flip a parasitic relationship to one of symbiosis. For readers (like myself) wondering how this can be accomplished without killing the blight, a paper linked in the article goes into detail on this subject: their method “provides ‘tolerance’ to the blight not by killing the pathogen, but instead by protecting the tree from the damaging oxalate produced by the pathogen. The tree and the fungus can coexist, as is the case with Asian chestnut species in the native range.”

This flip back to the blight’s natural (Chinese) chestnut symbiosis can work because the fungus does not need to damage chestnuts in order to survive; therefore, creating a blight-resistant chestnut would not deprive the blight of sustenance. The blight doesn’t damage trees “on purpose”, in order to gain nutrients from it (unlike other pests, like the emerald ash borer or hemlock woolly adelgid). Instead, the damage is a side effect of the fungus’s natural processes, which don’t usually harm its native host (the Chinese chestnut).

Karen Kemirembe

Entomology

Awesome article. I now know more about chestnuts than I ever did, and I love your use of the historical and futuristic perspective. You noted that “Some people are arguing against its approval due to lack of long-term studies of the modified tree’s impact on the environment” which is an interesting position because failure to do anything could lead to the tree’s extinction which could lead to an even bigger environmental impact than the modified tree.

A few lingering questions I had were the following: