Uranus emits extra x-rays, and scientists don't know why

They could be just reflections, or Uranus could have its own version of the Northern Lights

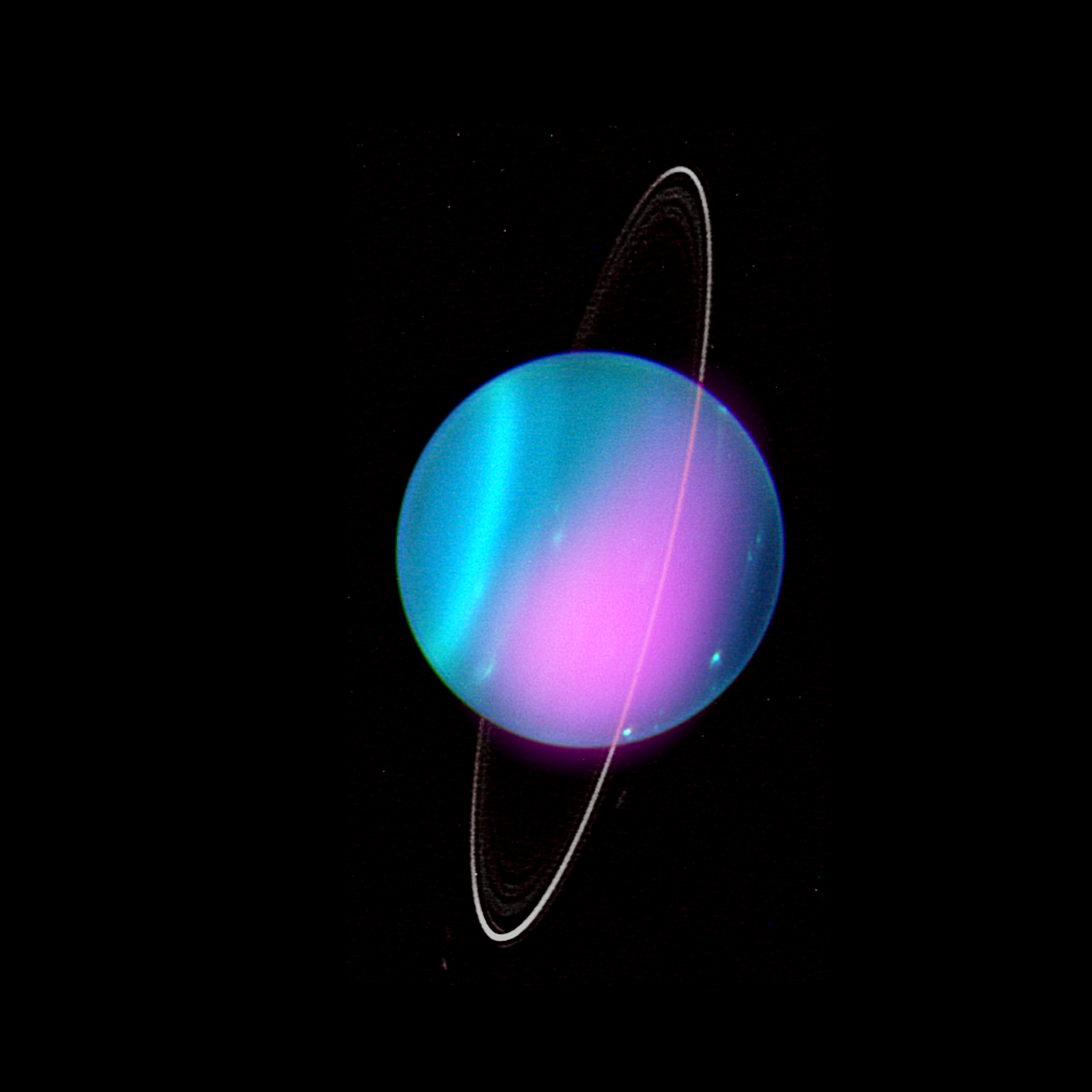

Chandra image gallery. X-ray: NASA/CXO/University College London/W. Dunn et al; Optical: W.M. Keck Observatory.

Scientists have recently discovered x-rays coming from the planet Uranus. Using data from the Chandra X-Ray Telescope, scientists have observed x-rays on Uranus in images from both 2002 and 2017. (You might be thinking, “2002, how is that new?!” Sometimes, like in this case, astronomers will record a lot of data and not actually finish analyzing it until years later).

They combined this x-ray information (shown in pink) with optical pictures of Uranus (blue), resulting in the image you see here.

Combined optical and X-ray image of Uranus

Chandra image gallery. X-ray: NASA/CXO/University College London/W. Dunn et al; Optical: W.M. Keck Observatory

High energy x-rays from a planet might sound shocking, but we’ve actually seen x-rays coming from most planets in the solar system. The Sun emits x-rays, and planets reflect some of that light back into space. The interesting thing with Uranus is that it seems to show more x-ray than you’d expect from just reflected sunlight. So, how is Uranus producing extra x-rays? Maybe it simply reflects more x-ray light than the other planets, or maybe it has charged particles hitting its rings, like Saturn. Another explanation could be aurorae — like the Aurora Borealis on Earth, other planets emit light when charged particles (like electrons) travel along the lines of their magnetic fields.

Either way, we’ll need more observations to know for certain what’s going on with Uranus. We know quite a bit about our solar system, but the two ice giants (Uranus and Neptune) are woefully unexplored. The only mission to visit them was Voyager 2, back in the 1970s, and we haven’t been back since.