Are some of us hard-wired for compulsive drinking?

Brain activation can predict compulsive alcohol consumption (in mice!)

Photo by Wil Stewart on Unsplash

The persistent use of alcohol despite the negative consequences is widely accepted as one of the main behavioral traits in alcohol use disorder, and has also been considered as one of the more promising points of intervention. Despite the acknowledged importance, the neural correlates of compulsive drinking are not well understood.

But progress is being made. A sophisticated study recently identified a neural circuit in the mouse brain, the activation of which could be used to predict the emergence of compulsive alcohol consumption.

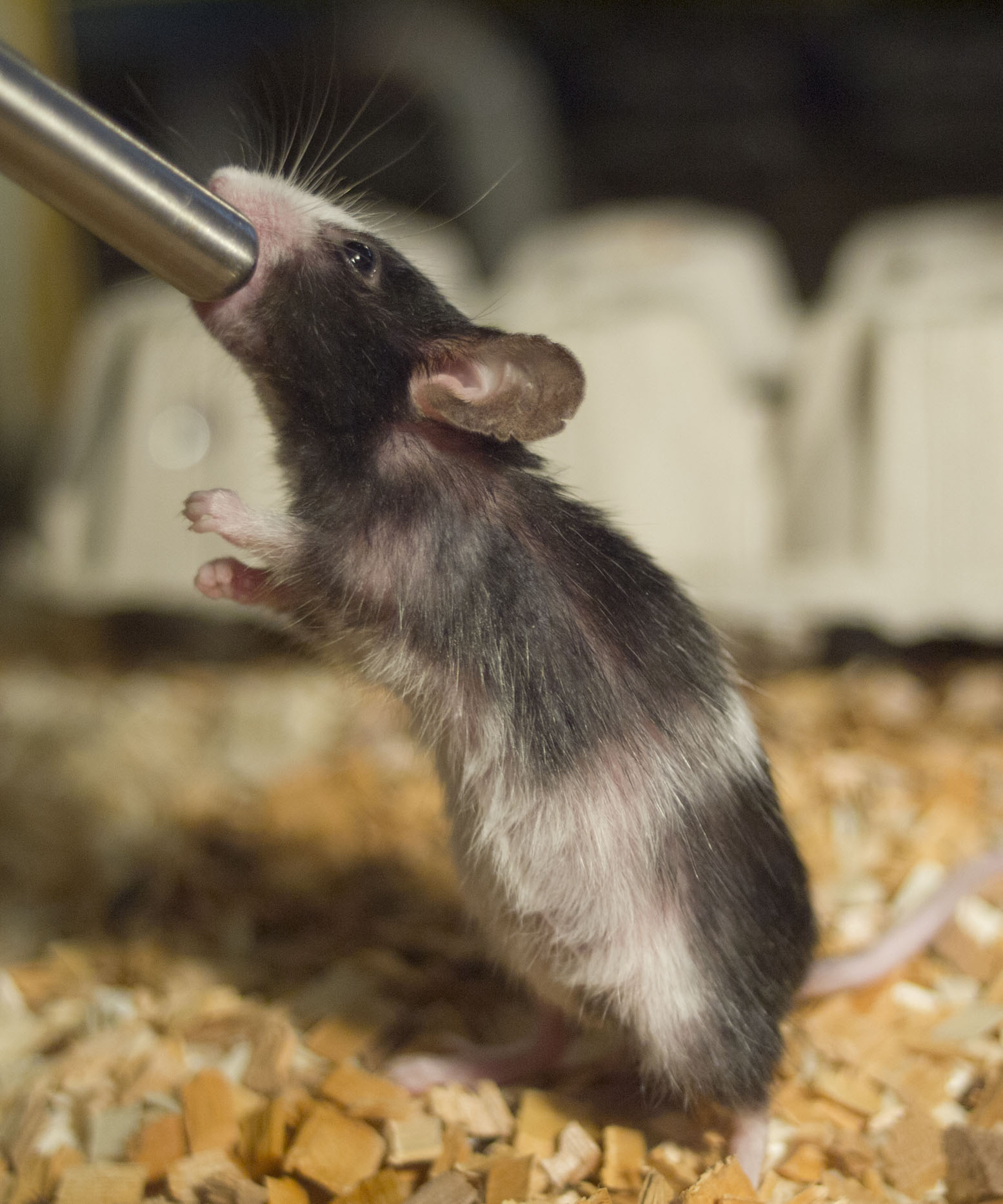

Tiia Monto on Wikimedia Commons

The researchers developed a new model where the mice first got to drink alcohol in small dispensed servings. Next, the mice got unlimited access to alcohol for few hours a day, for five consecutive days a week, leading to binge-like drinking behavior. After this, the mice were returned to the original setup with the smaller alcohol servings. Bitter-tasting quinine was then added to the alcohol in increasing concentrations, making the alcohol more unpleasant. Afterwards, the mice were categorized into three groups based on their drinking behavior. Low drinkers didn't drink very much alcohol. High drinkers drank lots of alcohol, but drank much less when the nasty-tasting quinine was added. Compulsive drinkers drank a lot, even when it tasted terrible.

The scientists then identified a neuronal pathway leading from the cortex to an area of the brainstem called the periaqueductal gray, and measured the activity of these brain cells during the first time the mice were exposed to alcohol. Remarkably, the activity patterns of these cells during the first phase of the test were strongly correlated with the drinking behavior in the post-binge phase. In other words, the brain activity patterns that the mice showed when they were first exposed to alcohol predicted which mice would later become compulsive drinkers.

While the clinical applications are not exactly right around the corner, it's possible that these results may be able to inform future treatments for alcohol use disorder.