Urbanization increases risk for knee osteoarthritis, even in young children

A study shows that rural children tend towards a healthier future for their joints compared to kids in cities

Many countries with agricultural-based economies are experiencing rapid urbanization as they transition to market-based economies. On top of the the broad societal changes experienced in these countries, research is studying the significant health consequences that this rapid urbanization can cause.

Many of the health changes associated with urbanization are thought to be a direct result from reductions in physical activity levels. As physical activity is well documented to be protective against many ailments, such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancer, urbanization has the potential to negatively impact human health. A recent study has indicated that the urbanization additionally may have widespread effects on the joints of its citizens.

In a study from Nicholas Holowka and Ian Wallace, Harvard University, the University of Buffalo, and the University of New Mexico, knee cartilage thickness was examined via ultrasonography in children living in both urban and rural Kenya. Western Kenya is an ideal location to study the effects of urbanization as many small communities still practice small-scale farming while being closely located to the more populated city of Eldoret. Children from ages 8 to 17 were recruited in order to see how knee cartilage thickness changed throughout childhood.

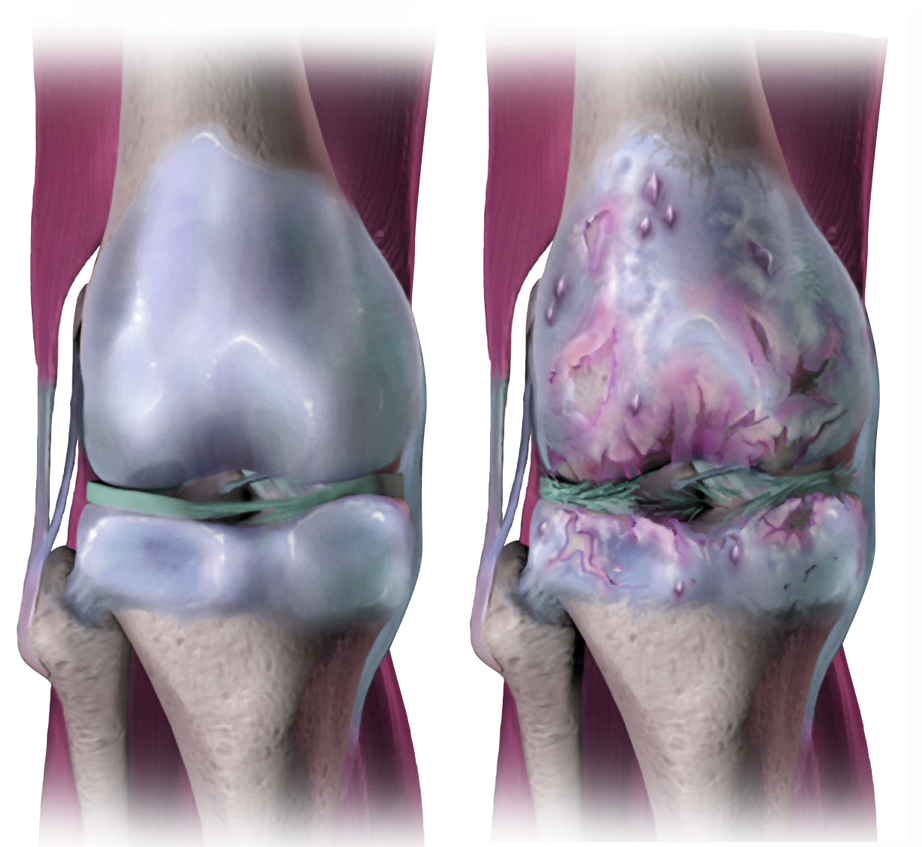

A diagram showing osteoarthiritis in the knee, with cartilage degrading and the joint narrowing in width in the knee on the right, compared to a healthy knee on the left

Via Wikimedia

As loss of knee cartilage thickness is a risk factor for the development of osteoarthritis, this study aimed to uncover any differences in risk for developing knee osteoarthritis later in life due to urbanization. Interestingly, despite the study focusing only on osteoarthritis, a disease often associated with old age, the rate of reduction in knee cartilage thickness was still significantly less in the rural children compared to the children living in an urban environment. For the urban participants, knee cartilage thickness declined an average of .11mm per year during childhood. However, the rural children only saw knee cartilage thickness reduced an average of .047 mm per year. These results suggest that urbanization results in a greater risk for knee osteoarthritis, which can be seen even within childhood. So what is causing this increased risk in urbanized children?

One hypothesis that has been suggested is that the increased risk of knee osteoarthritis for those living in urban environments is due to dietary changes and increased fat accumulation. This theory holds that the dietary changes of urbanization promotes low-grade inflammation from the release of adipokines from excess adipose tissue. Adipokines, such as leptin, are cell signaling proteins that are secreted from fat tissue and can promote inflammation throughout the body. However, as mentioned previously, there were no differences between rural and urban children in terms of BMI in the current experiment and yet, knee cartilage thickness was still reduced in children living in urban areas. This would be unlikely if obesity-derived low-grade inflammation was the main culprit for loss of knee cartilage.

A similar study as the current investigation conducted within an urbanized country may help provide more insight. This study revealed that there was an association with low levels of physical activity and decrements in knee cartilage thickness within children. Animal studies also confirm that decreased physical activity through unloading promotes a loss of cartilage, potentially due to metabolic changes in chondrocytes. In the current study, children who were overweight did not show a correlation in a reduction in knee cartilage thickness. Taken together, these results suggest that physical activity levels, but not obesity, are likely responsible for the decrements in knee cartilage thickness seen within urbanized environments.

For those living in an urbanized country with a market-based economy, these results are potentially troubling. The health consequences of urbanization likely extends far beyond just obesity, as seen by the current study. And these changes and risk factors are already present within children living in urbanized environments. Additionally, this study challenges one of the commonly held paradigms of what constitutes healthy living. So often the numbers on the scale are considered the gold standard measurement that reflect overall health and wellness. However, physical activity levels, regardless of fitness levels and BMI, may play an important role as well.

Indeed, osteoarthritis rates are very prevalent within the United States, especially within the aging population. As many as 10-13% of Americans over 60 will be diagnosed with osteoarthritis. As living within an urbanized environment has been shown to be correlated with reductions in physical activity levels, this may not come as a big surprise. However, research such as the current study is vital in providing a clear understanding of the health issues deriving from urbanization. As the topic is increasingly investigated and the wide-spread effects of urbanization on human health is understood more thoroughly, hopefully these challenges can be met with better preventative health measures.