Astronomers want the Thirty Meter Telescope on a sacred Hawaiian summit. But who is it for?

The TMT, through the lens of a Native Hawaiian

Brent Storm / Unsplash

Dull yellow street lights are a part of everyday life on Hawaiʻi Island, my hometown. These monochromatic lights keep the Hawaiian night skies dark, allowing for stars to shine.

The island of Hawaiʻi is home to Maunakea, the world's tallest mountain from base to peak. Measured from the seafloor, rises over 6.3 miles, about 4,000 feet taller than Mount Everest. With its summit perched high above the clouds and out of the way of the light pollution produced from the island population below, this site is one of the best locations in the world for stargazing. There are 13 telescopes present on the mountain top, and one more is in the works.

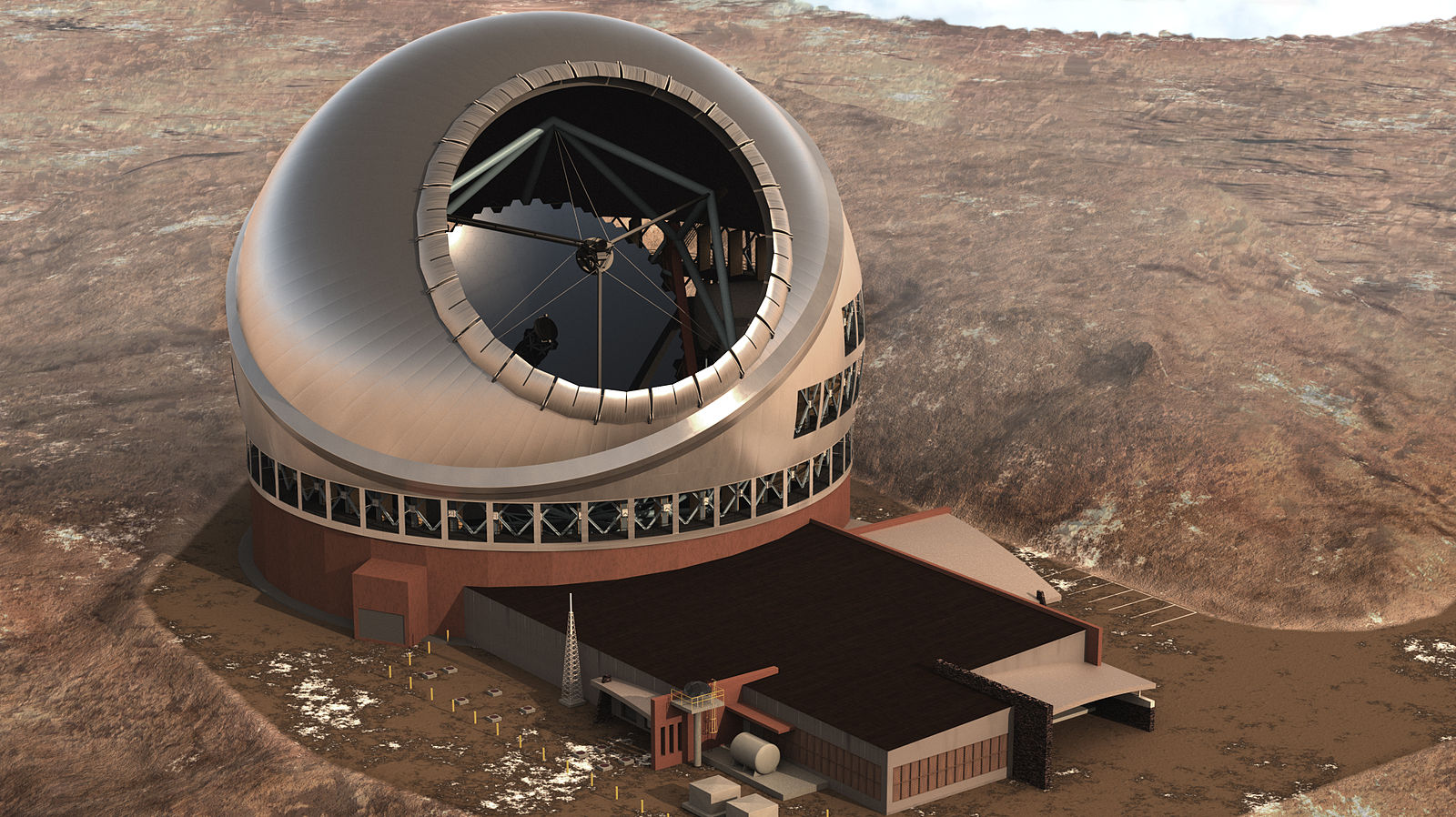

The location and conditions of Maunakea are significant to astronomers thanks to its high elevation, dry weather, and the greatest number of cloud-free nights of any mountain in the world. Being in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, its location gives astronomers the ability to see both the northern and southern sky. A proposed telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), will be 34,000 square feet and sit 18 stories tall and produce images 12 times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope. An international non-profit partnership, called TMT International Observatory, or TIO, is in charge of the telescopes design, construction, and operations. The TIO partnership consists of universities from Canada, China, Japan, India, and the US planning to explore the beginning of our universe, the physics of the early universe, and dark matter with this telescope. TMT will create additional jobs and revenue for the University of Hawaiʻi, but is this enough to overlook the religious, cultural, and environmental importance of Maunakea?

The proposed Thirty Meter Telescope.

TMT Observatory Corporation/Wikimedia Commons

American presence within the Hawaiian Islands, for the past century to the present day, suppresses the Native Hawaiian culture and population through imperialistic expansion, creating anger and distrust of some Western practices, including science. Hawaiʻi, as a whole, can provide a plethora of answers to the growing curiosity about the world, but only if the people and culture are understood and respected. The violence of the colonists who viewed Hawaiʻi as an opportunity to exploit, profit, and conquer echoes within the islands today.

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was a sovereign nation recognized by European powers and the United States. In 1893, the Kingdom had over 90 embassies and consulates throughout the world. The Kānaka Maoli, the Hawaiian people, were educated through the oldest public school system west of the Mississippi, founded by the sovereign monarch, King Kamehameha III. As the population and profits from the sugar industry grew in the Hawaiian Kingdom, greed and imperviousness quickly transformed into treason.

In 1893, a coup d'etat, supported by the United States, was organized by 13 foreign businessmen calling themselves the "Committee of Safety." The Committee of Safety forced Queen Liliuʻokalani, the last reigning monarch of Hawaiʻi, to abdicate. To avoid bloodshed and with the promise of releasing imprisoned citizens, Liliuʻokalani signed the abdication papers, abolishing the Kingdom. Following that, the people of the Hawaiian Kingdom were forced to abandon their native tongue and culture and learn the English language and American ideologies. It wasn’t until the 1960s that a resurgence of the Hawaiian language and culture revived what had been suppressed for nearly 70 years; the language, traditions, and the stolen Kingdom of the Kānaka Maoli will never be forgotten.

Astronomy is an integral part of wayfinding throughout the Pacific and is used in various everyday Hawaiian practices, such as the Hawaiian calendar, plant cultivation, and fish spawning. It is important to know that Kānaka Maoli worked in harmony with the environment without the notion of ownership or superiority. This concept is expressed in the Hawaiian proverb, "He aliʻi ka ʻāina; he kauwā ke kanaka" ("The land is chief; man is its servant"). Owning land is a Western idea, one that has no equivalent in the Hawaiian culture. From the first arrival of Westerners to the Hawaiian Kingdom until today, this balance between the land and the Kānanka Maoli has been destabilized. With well over half of the total land area in the state of Hawaiʻi owned by non-natives, the Hawaiian population is forced to watch sacred lands fall into the ownership of foreigners who disregard their culture and beliefs.

Maunakea is where the earth and sky meet. It is a dormant volcano, a physical place where religious and cultural practices transpire. It's seen as an ancestor of the Hawaiian people. A kuahu lele (alter) sits at the summit, symbolizing the connection between Akua (the creator) and ancestral ties to creation. It is also the home of nā Akua (deities) and nā ʻAumakua (ancestors) and a burial ground for high-ranking Hawaiian chiefs and Kahuna (priests). This place is the pinnacle of the Hawaiians’ connection to their past, a place that is now threatened and could be harmed in the future.

A Hawaiian altar stands at the summit of Maunakea, along with 13 telescopes

Brian W. Schaller / Wikimedia Commons

The proposed location of TMT sits within a sacred Hawaiian realm called Wao Akua, the realm of the creator. The Kānaka Maoli rarely entered this area out of respect for their ancestors and gods, as this space is dedicated to the deities that provide the Kānaka Maoli with life. Three historic altars lie within 1,600 feet from the planned telescope, made from igneous rock that could be destroyed during construction. In the eyes of the Kānaka Maoli, adding this telescope to the already limited space on the summit disrupts Hawaiian practices, disrespects the resting place for their ancestors, and upsets the balance of the land.

In ancient Hawaiian times, a disturbance to the balance of the land meant detrimental effects to the Kānaka Maoli: Any lost resource meant less food for the population. Protesters around the world stand with Maunakea as ku kiaʻi mauna, or guardians of the mountain, some of whom were arrested for participating in these demonstrations. This conflict between the Kānaka Maoli and the continued exploitation of our land is an issue that will not disappear if the construction of TMT is canceled. This publicity has brought the world's gaze upon Hawaiʻi, giving us, as Kānaka Maoli, a chance to share our side of the story.

The Kānaka Maoli have been suppressed for decades, forced to watch their home fall into the hands of people who fail to listen to us. This repeated cycle of exploitation, profiting, and conquering is not specific to the story of Hawaiʻi, but to many other native populations. Being a Native Hawaiian scientist, I am convinced that Hawaiʻi and the mindset of the Kānaka Maoli would add diversity to the world of science. The Hawaiian Islands could make world-changing impacts with the broad resources, diverse climates, and extensive knowledge the Kānaka Maoli have.

Before stepping into any land you must hear the native people and understand their story — native culture is not expendable in the quest for knowledge. Science must work with the culture, not against it.