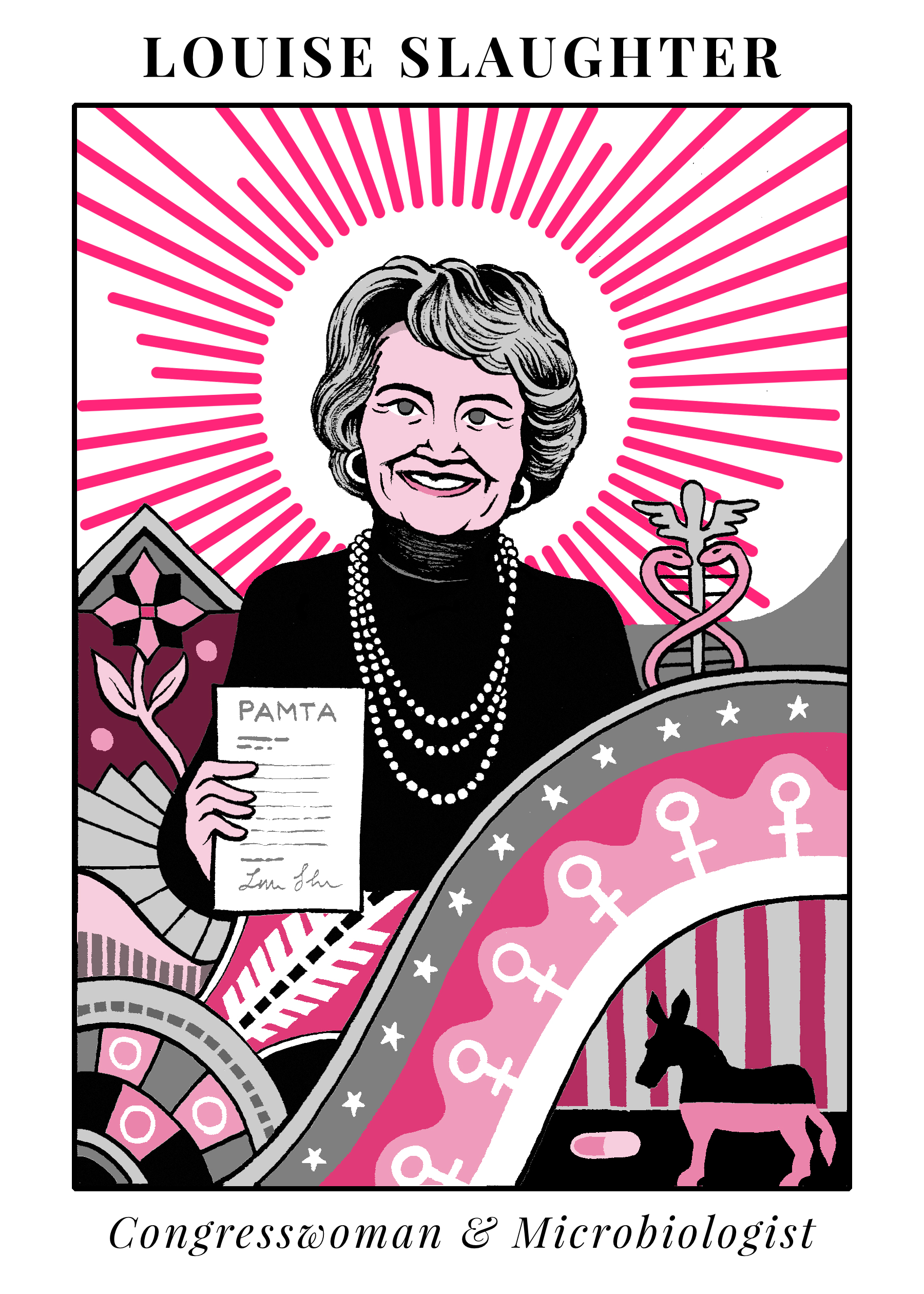

Three times Louise Slaughter used her microbiology training in Congress

The lawmaker, the only microbiologist in Congress, pushed for public health reform

Matteo Farinella

When Louise Slaughter first became a member of Congress in 1987, she brought science and gender equality to the limelight in politics.

Slaughter passed away last month at 88, as the oldest sitting member, and the only microbiologist in Congress. She was also the first woman to chair the House Committee on Rules, from 2007 to 2011.

The death of her sister from pneumonia as a child spurred Slaughter to pursue the sciences. With a bachelors degree in microbiology and a masters in public health, she began working for Procter & Gamble doing market research soon after graduation. During this time, she became increasingly involved in local politics and community issues, as an active member of the League of Women Voters and local environmental groups. First beginning her political career in the Monroe County Legislature and subsequently the New York State Assembly, she was a champion for homeless children, women’s rights, and environmental protection.

Matteo Farinella

Here are three notable pieces of science-related legislation she spearheaded during her two decades in Congress.

Inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials

In the past, nearly all research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was done on white males – even studies and clinical trials related to predominantly female disease. Medical researchers were encouraged to include women in clinical studies, but this rarely happened because it was not enforced.

Historically, women were excluded for several reasons. Cyclical hormone differences would complicate studies by adding another variable to experiments. Another reason was that a number of diseases were thought to be largely “men’s disorders.” Cardiovascular disease was known as a “men’s disease” even though it is the leading killer of both men and women in the US. And exclusion of women in clinical trials was said to protect them from risk during child-bearing years. This all meant that treatments didn't (and don't) necessarily have the same efficacy in women.

Slaughter co-sponsored the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, which mandated the inclusion of women and minorities in all federal health clinical trials. This led to the establishment of the Office of Research on Women’s Health at NIH in 1990. The NIH awarded her its “Visionary for Women’s Health Research” award 10 years later.

Today things are improving, slowly. Diseases often present differently in men and women, but reported research still frequently fails to account outcomes by sex. Even today, when we think of “women’s health,” the first thing that come to mind is women’s reproductive health. But in actuality, women’s health encompasses far more than that.

Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act of 2008

Genetic discrimination occurs when people are treated differently due to a gene mutation that increases the risk of an inherited disorder, by the likes of employers and health insurance companies.

Slaughter began working on a bill to combat genetic discrimination in the early days of genome sequencing. But getting the bill – the Genetic Information and Non-Discrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) – signed into law took perseverance. Slaughter introduced GINA and its previous iteration repeatedly for over 14 years before it was signed into law on May 21, 2008, five years after the completion of the Human Genome Project. Now, employers and health insurance companies are prohibited from discriminating based upon genetic test results.

However, GINA does not protect us from all genetic discrimination. GINA is specifically limited to employers and health insurance companies. It does not cover life, disability, or long-term care insurance. Now, as companies such as 23andMe and Ancestry DNA have started to provide genome sequencing services directly to consumers, the holes in GINA are becoming clear: consumer privacy policies vary from company to company, and consumers often do not read the fine print.

Antimicrobials stewardship

When farmers discovered in the 1940s that adding low doses of antibiotics in animal feed protects healthy animals from getting sick and speeds up growth, antibiotic use in agriculture became mainstream in the US and worldwide. Animals grew quickly, meaning they could be butchered faster than before. But this comes at a cost. Nearly 80 percent of all antibiotics used in the US are for agricultural uses, fueling the spread of antimicrobial resistance amongst animals and humans.

“When I was doing microbiology in college, Staphylococcus aureus was the most innocuous bacterium you would ever see," Slaughter said in a 2015 interview with Vox. "Now it has evolved to become methicillin-resistant, also known as MRSA, and it can kill you in 24 hours.”

Slaughter did her master’s thesis on the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in 1954.

“I've been sounding the alarm to the growing threat of antibiotic resistance for a long time,” she wrote in the American Society for Microbiology’s Cultures magazine. ”Unfortunately, because of decades of lobbying by corporate interests and a flat-footed response from government, antibiotic resistance is now one of the most pressing health crises of our time.”

Slaughter made the Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act (PAMTA), which was designed to limit antibiotic use in livestock feed, her signature legislative issue in 2007. This would also phase out the use of eight major classes of antibiotics in healthy, food-producing animals, allowing their use only for the treatment of sick animals. She reintroduced this piece of legislation in every subsequent session of Congress, but has been met with resistance by lawmakers beholden to the agricultural and pharmaceutical industries.

The strides in science policy from Louis Slaughter reminds us that science must have a place in politics – as science changes, the policies in play need to reflect our growing knowledge.