In science, failure can be a blessing. Just look at Viagra

The little blue pill started life as a failed treatment for chest pain

When I started my PhD four years ago, I had a lofty goal: I wanted to do medical research that could be directly translated into clinical practice and potentially help millions of patients down the road. But I quickly found that solving the puzzle of nature isn't easy or straightforward. In fact, the process of scientific discovery is rarely linear: an “aha” moment might not arrive after weeks—or even years—of failed experiments.

But failure can, in the end, be even more important to the research process than straightforward successes are. That may sound like an internal pep talk after too many late nights in the lab, but it's true: consider Viagra.

In the mid-1980s, scientists from Pfizer were working on developing a drug to help people suffering from angina, or severe chest pains caused by narrowing of the vessels carrying blood to the heart, preventing enough blood from getting through them. Unlike plumbing, vessels can adjust to the intensity of blood flow in any given part of our bodies by constricting and dilating. But if something in this process goes wrong, it will cause damage sooner or later. So the challenge doctors faced was: how can we help relax the blood vessels to restore full blood flow?

We can start by understanding how vascular dilation works, and that begins with a chemical called nitric oxide (NO). A gaseous molecule naturally produced in our bodies, it acts on smooth muscle cells that make up the walls of blood vessels and prompts them to relax.

There was already one effective way to treat angina back when scientists started developing the drug that eventually became Viagra. Think about nitroglycerin, which ER doctors give to patients with dangerously high blood pressure in emergency scenarios. When ingested or injected, nitroglycerin works by releasing molecules of NO that quickly dilate blood vessels and lower blood pressure. But this kind of drug can't be a long-term fix for chronic angina, because prolonged use makes bodies less responsive to it, making larger and larger doses needed over time to produce the same effect. (It's somewhat similar to why opioid addicts tend to seek out increasingly bigger doses.)

To deal with this limitation, scientists sought to develop a drug that would induce vasorelaxation in a different way: rather than manipulate the levels of NO, they could simply make its effects last longer.

Pfizer scientists found that a drug called Sildenafil was effective in laboratory settings prolonging the life of NO in animals, lowering their blood pressure as expected. Encouraged by promising results, Pfizer recruited healthy human participants to test the drug in 1991.

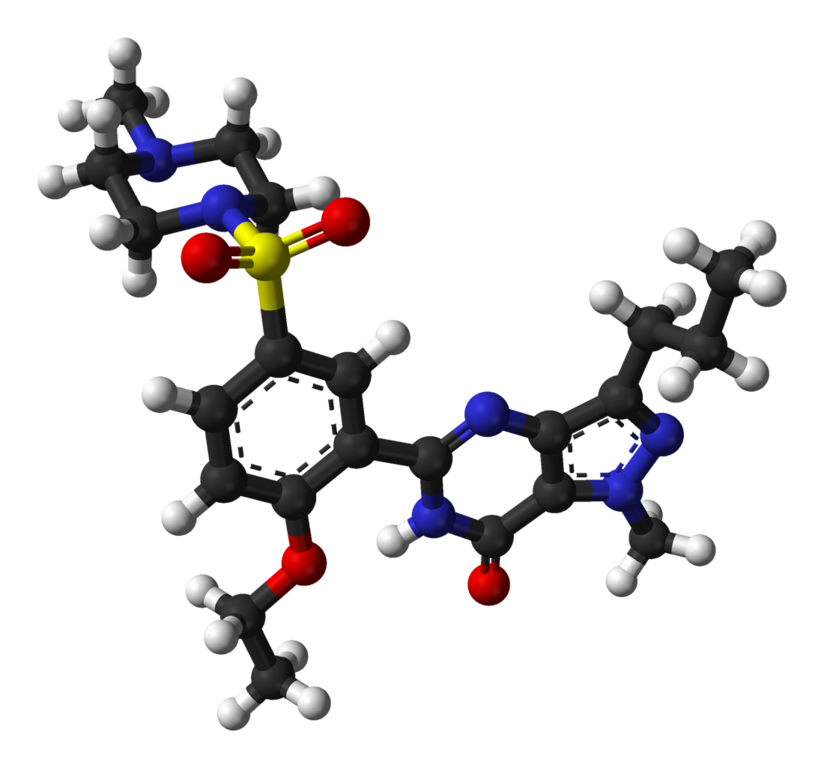

Ball-and-stick model of the sildenafil molecule.

Image by Ben Mills via Wikimedia Commons

It quickly became obvious that, because of how fast Sildenafil is metabolized by the body, patients would've had to take it at least three times a day to keep their chest pain in check. That's way too much to expect patients to do consistently. The clinical trial was swiftly terminated; no company wants to invest money into something that has a less-than-perfect probability of success.

Dr. Ian Osterloh, a British investigator who was leading the team of Pfizer scientists on a Sildenafil drug development project, recalls,

In one of the studies undertaken, male volunteers also reported increased erections several days after the initial dose. None of us at Pfizer thought much of this side effect at the time. I remember thinking that even if it did work, who would want to take a drug on a Wednesday to get an erection on a Saturday?

Serendipitously, around the same time, a lab at Johns Hopkins discovered that an enzyme that produces NO is present in large quantities in the nerves of a penis.

Fortunately, all research labs keep extensive documentation of every experiment that was ever performed and every observation ever made. In my lab, we keep stacks of hardbound notebooks stamped with our institution logo on the cover and filled with handwritten accounts of daily work dating back many years. This ensures that no information is missed and allows us to trace back mistakes, if needed, or to verify results. Documentation is also essential to prove intellectual ownership and apply for a patent.

Intrigued by Hopkins group discovery and going back to the old clinical trial notes, Pfizer scientists looked at their old observations through the new eyes. It turned out that the drug caused the same vasodilation – vessel relaxation – in the corpus cavernosum, the expandable tissue along the length of the penis which fills with blood during erection, as it does in vessels by the heart. It wasn't considered significant during the initial trials because this effect didn't last long, making it a minor side effect for a drug that was supposed to treat chest pain.

When they decided to test it for erectile dysfunction, a bug became a feature.

"When the results finally came through they exceeded our wildest expectations," Osterloh recalled. Sildenafil produces effects that are strong and consistent, that only work when needed, and that last through sex but not long enough to cause pain.

After a new set of successful clinical trials, Sildenafil was put on the market as Viagra in 1998. By 2005, a mere seven years after its launch, over 750,000 physicians prescribed Viagra to 23 million men in the U.S. alone. Between 2005 and 2016, Pfizer's worldwide revenue of Viagra sales reached $21.7 billion.

But the story doesn't stop there: in the past decade, a slightly modified molecule of Sildenafil became one of the key medications used to treat pulmonary hypertension, where blood vessels of the lungs become narrow and clogged, keeping sufferers from getting sufficient oxygen. The drug has gotten a third life as an effective treatment for a severe and deadly disease. Sildenafil works by dilating only the small lung vessels, and avoiding the bigger ones that don't capture oxygen from the air. This then helps patients breathe more efficiently.

But even this is not the end of the story. In the last five years, scientists have started looking at the possibility of using Sildenafil for the treatment of other cardiovascular conditions, such as heart failure and even stroke—the drug has shown promise in the restoration of brain function in rats.

Viagra may help hearts—and even minds—after all, but scientists only figured this out by continually finding new ways to approach existing data. That is, they succeeded at failing.

I like to remind myself of this after yet another late night in lab.

Featured Article

- Ghofrani HA, Osterloh IH, Grimminger F. Sildenafil: from angina to erectile dysfunction to pulmonary hypertension and beyond. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2006;5(8):689–702. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2030