To shop sustainably for clothing, stop shopping

Even clothing recycling and rental programs don't reduce CO2 emissions as much as just wearing the clothes you have

Arturo Rey via Unsplash

When COVID-19 hit, it seemed like the world moved online — and stuck in quarantine all day, many turned to online shopping. Retailers reported a 14% increase in online shopping among people under 30 during the pandemic. Some saw even more dramatic increases; Boohoo, a predominantly online retailer, reported a 45% increase in sales from March 2020 to May 2020.

While the pandemic certainly gave online shopping a boost, online retailers are also rising in popularity because they are well-equipped to quickly pivot between trends, and provide trendy clothing items at a low price point. But an increase in online shopping also means increased waste and carbon emissions.

Global clothing production has doubled in the last 15 years, but the number of times a garment is worn has decreased by 36 percent. Even more shockingly, 73 percent of textiles end up discarded in a landfill. Fast fashion, an approach to clothing manufacturing and marketing that emphasizes making fashion trends quickly and cheaply available to consumers, has compounded the problem by setting the expectation that something may only be worn once — which is terrible for the environment, considering the impact of manufacturing and shipping clothes. There is, to put it plainly, way too much clothing being produced. It's past time to figure out more sustainable practices for reusing or disposing of clothing.

It can be difficult to figure out how to introduce sustainable practices into your wardrobe. Some companies make their clothes from recycled materials — but does this really reduce their impact? And once you have outgrown or over-worn items, is it better to donate clothes to thrift stores or use textile recycling services? According to new research out of LUT University in Finland, the best way to shop sustainably is to simply buy less.

Although they may not realize it, consumers often think of clothing consumption from a linear economic perspective: raw materials are turned into goods, which are then sold, and eventually disposed of. Of course, most people also know that there are alternatives to simply throwing away clothing when it no longer serves them. Donating to a thrift store is an example of the classic "reduce, reuse, recycle" approach, which economists refer to as a circular economy. Circular economies have been touted as a way to help society become more sustainable while decreasing environmental and energetic costs. Creative circular economy practices, including clothing rental services, and clothing made from recycled, rather than new, materials, have been proposed in recent years as ways to increase fashion sustainability. But how do these new innovations compare to the old standards for sustainability?

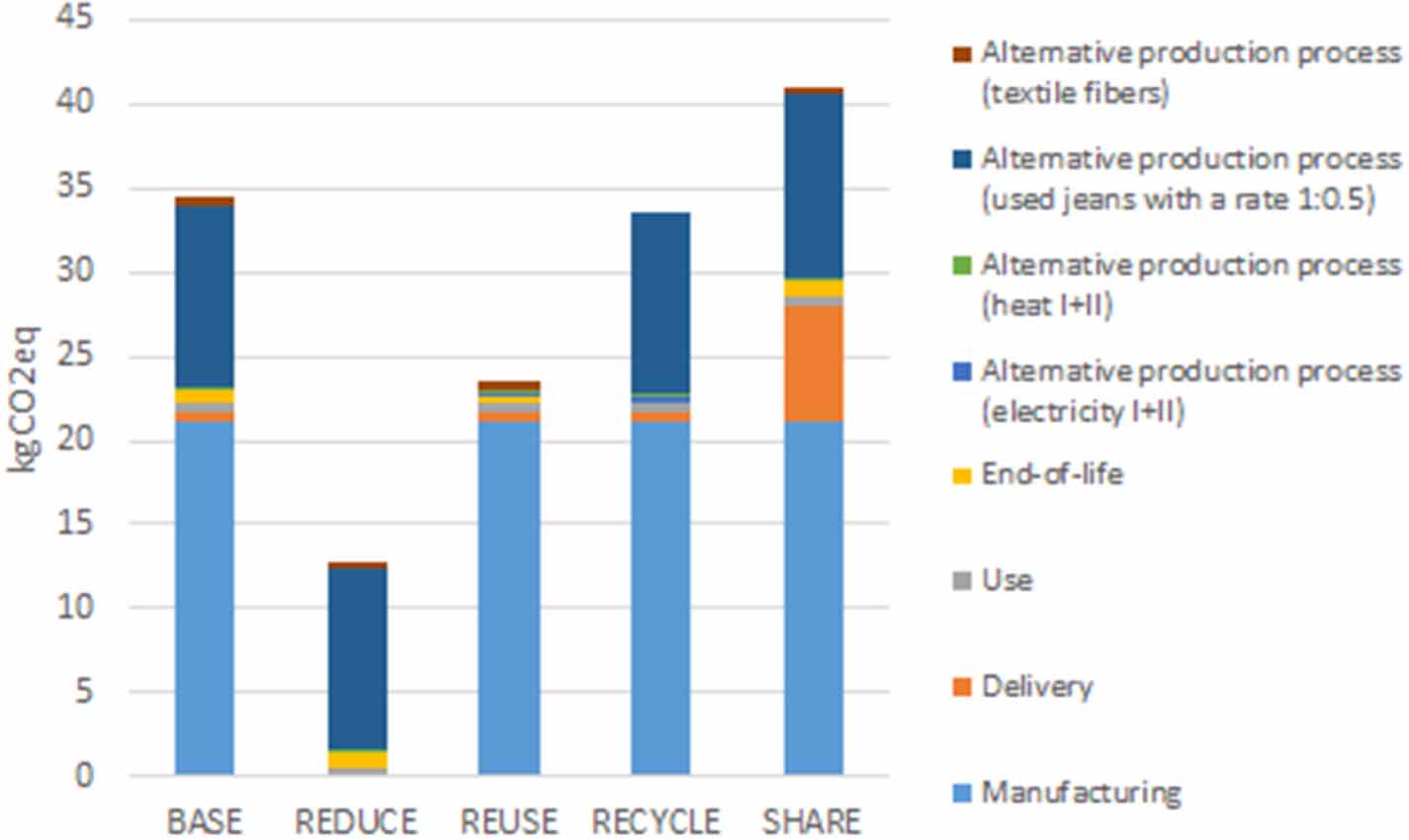

The researchers considered the carbon impact of these "new and improved" sustainability practices by calculating the emissions produced at different stages in the lifecycle of a pair of cotton jeans — through its manufacturing, delivery, use, and disposal. These calculations were based on 200 wears. The researchers then compared "end-of-life" scenarios for the jeans, including extending their use beyond 200 wears, re-selling them at thrift stores, and manufacturing them from recycled clothing materials. Jarkko Levänen, lead author on the study, says that choosing jeans and CO2 emissions "left some other dimensions of sustainability out of [their] scope, but...allowed them to go deeper in the analysis."

A chart showing that, compared to changing nothing (base), reducing the amount of clothing purchased is the most effective way to reduce CO2 emissions associated with clothing manufacturing

Levänen et al 2021

Ultimately, Levänen's team found that the best way to shop sustainably is to limit the amount of clothing that you purchase. The results showed that manufacturing new clothing produces over half of the total carbon dioxide emissions associated with a garment — meaning that even sustainable disposal practices can't overcome the initial environmental impact of making a new piece of clothing.

Simply put, purchasing fewer pieces of durable, high-quality clothing, and then trying to wear them as many times as possible, is the best way to reduce your environmental impact. Levänen states that their findings generally align "with the existing knowledge on sustainability implications of the textile industry as well as uncertainties that come along with new types of business models."

While that may seem like common sense, the researchers also found some surprising results. For example, using recycled textiles is popular in the fashion industry right now, and many companies proudly state that their fabrics are sustainable because they are made from recycled plastics. However, the researchers found that using recycled textiles doesn't substantially reduce environmental impact, because the production of cotton generates fairly low emissions, compared to the emissions from recycling processes needed to make synthetic fabrics.

They also found surprising results when they calculated the emission for rental companies. renting clothing increases the number of uses for a garment (a good thing!), but can also rack up emissions from transportation if the rental is not from a local area. Consequently, clothing rental services that relied on shipping actually had higher associated carbon dioxide emissions than if the clothes were just thrown away. Of course, these results come with a fair amount of nuance — if clothing delivery can be arranged via biking or walking, then sharing reduces environmental impact as much as re-using clothes.

Ultimately, it's important to shop mindfully in order to help reduce garment production. Overall, Levänen reminds us to reflect on consumer behavior and the necessity of buying new clothes, pointing out that "in the big picture, even small changes in consumer behavior play critically important [roles]."