How should we live in the era of climate change?

Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson speaks about social tipping points, women in climate research, and how to prepare cities for the coming climate crisis

Photo by Riaan Myburgh on Unsplash

This week is Climate Week, coinciding with the UN Climate Change Summit. On September 25th, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will release its newest report. Every day this week Massive will be publishing articles and interviews with scientists, policy experts, and activists about climate change, all aspects of the new report, and the future of the planet.

A world that is more than 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer is a very different world than the one we live in today. From rising sea levels to dramatic declines in fisheries, some of the biggest impacts of climate change will be felt in the oceans. Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, marine biologist and conservationist, is working towards protecting ocean ecosystems while also helping coastal cities prepare for the reality of continued climate change. She is the founder and CEO of the conservation consulting firm Ocean Collectiv as well as the founder of the climate adaptation think tank Urban Ocean Lab. She spoke with Massive Science co-founder and CEO Nadja Oertelt about community-level climate action, women climate leaders, and why increased access to the arctic isn't something we should be excited about.

Nadja Oertelt: What can we do given the US's lack of participation in the [UN climate] summit?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: To me it's astounding because climate change is one of the only problems you can't buy your way out of it, right? Your money won't save you. You can buy better health care, you can buy better education. You can buy better food. But when it comes to climate, we're really all in this together. And the lack of real national-level, international actions belies the inability of our leaders to get their heads around the fact that this will screw them over too. I think people think that they'll be okay, maybe other people will suffer, but they'll be okay. And that's just not true.

You could maybe buy yourself a little time. You could maybe buy yourself a private firefighting service, when your part of California starts to go up in flames more often. But [climate change] is coming for everybody. So that's something that keeps coming into my head, that this is a very different sort of problem. And we really are all in it together, which makes it seem somehow a bit more likely that we address things. But once people realize no one's safe, the rich, the powerful, we're all going down together. I think we might actually build more goodwill and inertia to do something about this.

Seeing the spectrum of people at the climate strikes, the diversity of people participating in this movement - there does seem to be a growing awareness that this is an all-hands-on-deck moment. A lot of people who have not been involved before are trying to find ways that they can plug in and be part of solutions and that's really encouraging to see. Can we actually avoid disaster without national and international coordinated, visionary leadership action? I think the answer is no. It's just a matter of exactly what that disaster looks like. So this new report put a finer point on, in more detail, what we can expect if we do or do not do certain things.

And so yes, it's not new. But it is a really important synthesis of where the science is. We don't know exactly what date sea level will be at exactly what height, but we do know it's rising and has been rising steadily since 1970. We do know that that's accelerating. So there's this opportunity with the report and a moment like this where people are finally paying attention to think about how citizens, collectively, can demand change. I think the lever that doesn't get talked about enough is how social pressure can shift corporate practices in the absence of government work. So I think we'll start to see more direct action and more forcing of corporations to shift, even when governments don't do their job and regulate them.

Maybe that's wishful thinking. But I think people are really going to try.

NO: I wonder at what point the rich and the privileged, who think they'll be able to buy their way out of this, actually feel the pain.

AEJ: I think when we think about tipping points, we're often thinking about scientific or ecological tipping points. But the point that you raised is that there are social tipping points, too. It's been really interesting to start to read a little bit of the social science of movements and how important a day like Friday and these massive climate strikes are, because it lets people know that they're actually not alone. They're amongst the majority of Americans who are also really concerned. That's the social tipping point where people realize they're not alone and they're part of a movement, so they can start to work together and in more active ways to start to change things.

But yeah, it's really scary. I don't know what's going to happen. No one knows what's going to happen. I mean we obviously know the generalities of what could happen. I think about is how to conceive of climate impacts as a spectrum and not an all or nothing. Because we think about like, "Oh we have 10 years," or, "Oh if this happens, we're doomed." And absolutely what we do in the next 10 years is critical. Absolutely there are some things that once we cross those ecological thresholds, they won't come back, like coral reefs, potentially. Once a species goes extinct, that's it.

But the health and habitability of our planet is a spectrum. And it really matters because zero is done. That's it. End of life on earth. A hundred is pristine. I don't think either of those are going to be the outcomes. So there's this huge spectrum in the middle where the science can help us figure out how to get us as close to 100 as possible. It sort of depends what side of the bed I wake up on, whether I'm like, "We can get 70!" Or, "I'll take 30." But the difference between even 30 and 35 matters so very much. Even if we jut think about climate refugees and storms: the difference between 30 and 35 might be one fewer category five hurricane. That really matters. Or a foot less of sea level rise. And that really matters

We actually do need to care about every 10th of a degree. When the last special report came out with a projection of 1.5 degrees of temperature rise, we latched onto that number, as if that's where we were going to go, as if it would just stop there. But we're heading towards two, three, four, five unless we get our act together. That's just extremely dangerous. We knew how bad it would be at 1.5.

But it doesn't really change my work, because my work has always been, "How do we make things better?" It's never been like, "I'm going to save the world," right? Or, "We're going to save the world." So that doesn't change. And my new focus on coastal cities, it's still really important to think about how are we going to manage this transition for people who live in what are going to become increasingly dangerous places. A third of Americans live in coastal cities, and we are not prepared for what's coming. Because it's naivete that we can hold back the entire ocean somehow. That's just not going to happen. So we need a plan B.

Photo by Ashley Satanosky on Unsplash

NO: Are there examples of local citywide action around some of the issues brought up in the report, like sea level rise and the increase of intensity of storms? Are there good examples out there that you're using in your work to think about how, in the absence of global action, cities and people in those cities prepare or fight for certain types of legislation or policy that will help?

AEJ: The one that comes to mind right now is when we're talking about sea level, a lot of people look to the Netherlands, it's a country below sea level and they've been dealing with levees and dikes and gates for a long time. So I used to point to them and say, "Look, America's so much bigger than Holland. We can't do that. That's not viable for most places." Just the expense of installing these massive infrastructure projects as well as just the expanse of it being prohibitive.

So I learned recently though, that there is a program or an initiative in the Netherlands called Room for the River. The idea is, as sea level rises, the river's going to flood more often. The flood plain is going to expand. So they're actively thinking about how to move buildings and infrastructure out of that area. There's a transition plan to make room for the river. That's the kind of thing I wish more places were thinking about.

Inevitably, more places are going to be inundated and flooded even if that's inland in the United States, as we saw with the insane flooding this year in the Midwest. We know where the places are that are dangerous, and I would love to see more community- and city- and state-level action on developing plans to transform the way we live in those places. Maybe that should become park land instead of places where there are homes and city buildings and important infrastructure.

Until we actually come to grips with the fact that these changes are real and inevitable, no one's going to do anything because it's expensive and it's scary and it seems like a big risk, but the bigger risk is obviously just doing nothing. There's no excuse for that at this point. We have so much good information and so much science. We even have city and state and local level projections.

NO: Is the hope that you have local action at scale? I think it's pretty crazy that there's not a single example of a coastal city in the U.S. that's trying to take these mitigation steps seriously before terrible things happen. What's holding everyone back?

AEJ: Certainly federal policy is really important, but these are also discussions that communities need to have. They need to talk about places that are meaningful to them culturally, where generations of people have lived or fished or learn to ride a bike. I try not to read these reports and forget about the fact that there are real people whose lives are impacted. I think this report does a really good job of talking about how people will be affected by the decline in fish populations, how many people's food security is at risk.

NO: I wonder if that's the next phase of this particular movement, that people will move towards pragmatic action on a local, city-wide level.

AEJ: It is kind of sad to think that that's kind of where we've ended up. We have so little leadership and so little willingness to grapple with these big things that it's just not happening from the top down, but it at the same time it's sad. It's kind of always been that way. That the leaders get their ideas and political will comes from the ground up and the case studies and the ideas for things that could scale come from the ground up. That the concept of Urban Ocean Lab is not just coastal cities, yes, but how can coastal cities be a laboratory for what is possible at the state and federal level, too?

I think one of the things about Greta Thunberg that is so important has nothing to do with her and everything with the fact that other people decided it was okay to follow her, other teenage girls were like, "That's a good idea. I'm going to strike, too." I think we're in this moment where positive trends, environmental trends are catching on super quickly. Not everyone has to do their own thing. I'm encouraged by that.

I think I told you about this trip that I curated and facilitated along with Katherine Wilkinson, this retreat of 30 women climate leaders for a week at a ranch in Montana, and we made this video manifesto.

NO: I saw it last week when it came out. I thought that was really impactful.

AEJ: Oh good. That's good to hear. To me, that's important because it shows the spectrum of people that are working on this, not just all the different faces, but all the different areas of expertise and all the different reasons that people are getting involved in this. It just is one example of how people are really connecting so many different dots. To me it kind of symbolizes this shift that we need. Not that women have all the answers, but for sure if we ignore 51% of the planet, we're going to ignore some really good solutions.

NO: We have destroyed a common resource. Collectively we've made a massive error. Not just scientists or people who are working to understand the environment, but all of us. We didn't understand the trade-offs that we were making, and now we have to suddenly make a really abrupt shift in the way that we engage with the world. We can't look at growth in the same way. We can't look at stability in the same way. Interestingly, women have never really been in charge, but maybe the only way that we can sort of move into this new way of engaging is through a real kind of feminist leadership or feminine leadership.

AEJ: I mean it's worth a shot, right? We haven't tried it yet.

NO: Yeah, exactly. It's like the one thing that we haven't tried, but maybe it's the only way to move forward. What are we collectively trying to achieve in this moment? It's a goal that doesn't even fit into the current growth-minded framework. It's much more of a familial kind of collective goal and people can't process that at all.

AEJ: I love that word for this. Familial. Yeah. I think that's right.

NO: It's very interesting because to a certain extent, right now, it's more about the social response to climate change than it is about the science. We know what we have to do, but why can't we do it? That's not a scientific question, that's a social one.

AEJ: I think part of it is we're not going through the stages of grief. We actually need to mourn the things that we know we're losing and we're not. We don't have a cultural process for that, we need new traditions. We need ways to say goodbye to things. Then we can move on.

NO: There is a Japanese festival that I was reading about. It's a Buddhist and Shinto festival of broken needles. It's called Hari-Kuyo. You bring your broken sewing needles and your bent sewing needles, and you bring them to the shrine, and you say goodbye to them, and you thank them for their service. You put them all in a piece of tofu, and they're put to rest. It's also, traditionally, a way for women to mourn the labor that they put into making things or creating things and also to bury with those needles the secrets that they held.

AEJ: The secrets, oh, that's amazing.

NO: Isn't that so poetic and beautiful? We have very few well-known traditions around death or goodbyes that we can collectively engage with. There are a lot of indigenous and religious rituals, death traditions, that I'm sure we'll start to lean back on in these moments. But I wonder if there's also a space for building that kind of spiritual practice around the climate grief that we should all be allowing ourselves to feel.

AEJ: Yeah, I think that's exactly right. I mean, the mourning and the grieving, maybe that is part of this need for a more feminine approach, right? To say, "This is emotional. This is extremely difficult and painful." The upheaval that we're starting to actually viscerally feel, we need to process. It's not just sadness or depression. People are talking about climate depression and anxiety and these kinds of things. Yes, that's absolutely part of it, but for me it's like sometimes you need to cry when you read the science. I can't figure know what to do with those numbers until I've shed tears over what they could mean for humanity.

So I find myself crying a lot. Not weeping but allowing myself to shed tears because that is the way that I can acknowledge and release the pain associated with what we're doing to this planet and all these magnificent ecosystems and dynamics. I'm standing in the middle of New York City in a concrete jungle and being like, how crazy is it that we've built all this? It all is so tenuous, and I think it's important to stay connected to that and allow ourselves to feel all those feelings and use that as a way to remember why we do what we do and how high the stakes are and not let it overwhelm us. Or let it overwhelm you, but don't let it stop you from doing anything.

NO: Was there anything at all in the report that was surprising to you?

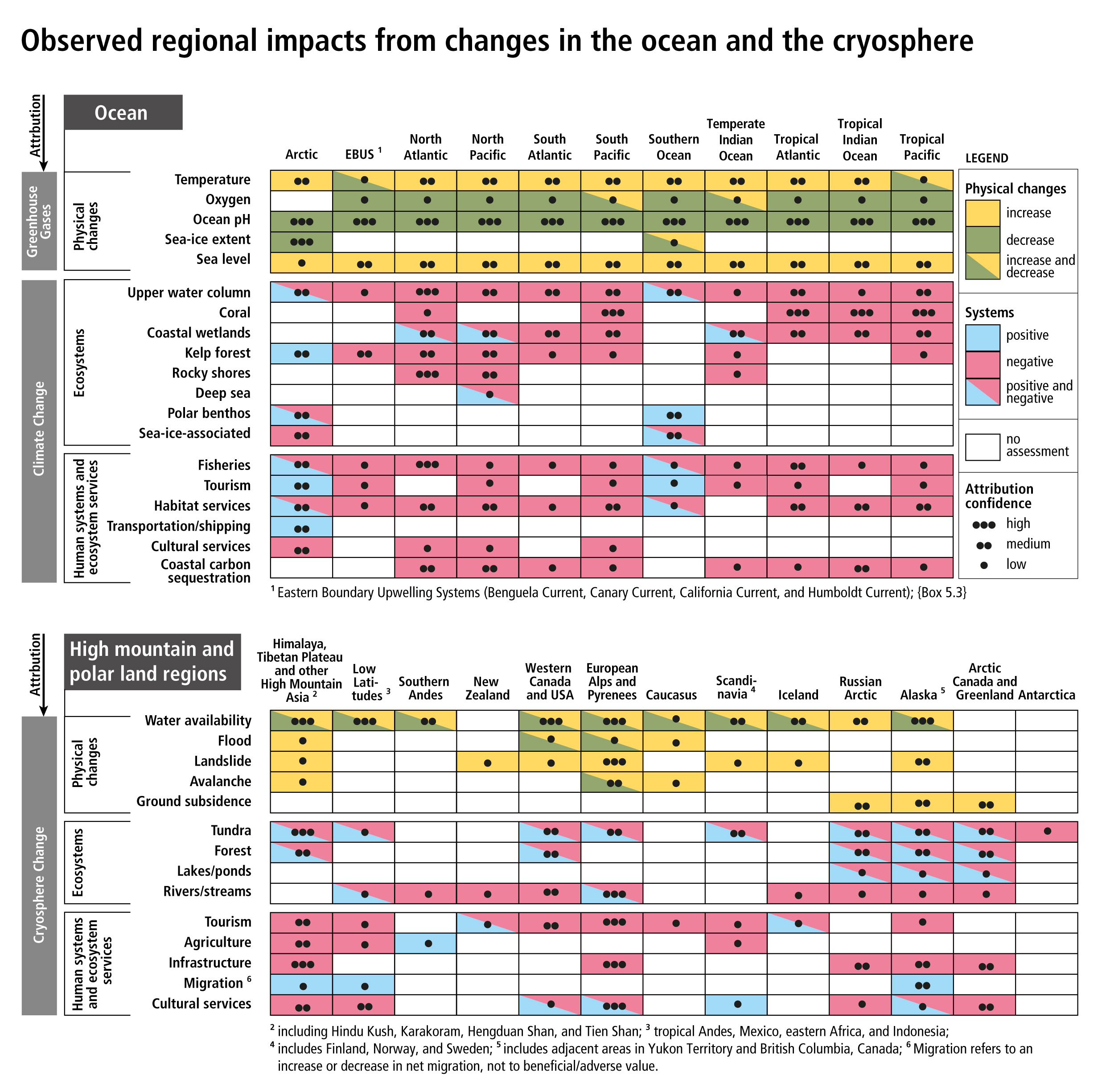

AEJ: That graph about positive and negative, I can't get it out of my head. The only "good" that will come of these changes is that the poles will be available for more tourism, which actually, that's not a good thing. It just means we can more easily access and therefore destroy yet another part of the planet. The thought of cruise ships in the Arctic is not exciting for me. And shipping. It's so interesting to think about the Arctic as a place where kelp forests will start to flourish.

Observed regional impacts from changes in the oceans and cyrosphere

IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere

That sort of blows my mind. Yeah. I mean, that's the thing that surprised me. Of course you could have extrapolated that yourself, but it was just so stark to see. I guess we can go on vacation at the pole! There's always that. What a weird silver lining, and it's not one at all in reality.

NO: You had a talk with Bill McKibben on Monday in NYC. How did that go?

AEJ: Something that came up is that we have a three generation movement now. He's been doing this stuff since the 80s, and now we have our generation, and now there's this younger generation that's super engaged. It's exciting to see because everyone has so much to add. There's people who have tried and failed at a lot of different approaches for decades. There's people my age who have been ramping up their work and are in positions of influence and building community. Then there's these kids who are just holding all of our feet to the fire, just keeping us accountable and keeping us pushing forward.

Between this report and the global climate strike the message is that we should be more brave and more bold in the work that we're doing and not tiptoe around or worry about scaring people or offending people. Just as I said in my talk at the strike, it's like we all need to be approaching this issue, the climate crisis, with the moral clarity of children. Some things are right, and some things are wrong, and we just need to not focus on comfortable-feeling compromises. That's just never going to be enough.

NO: I feel that as well. I felt that on Friday at the first strike. I think everybody was feeling it.

AEJ: But of course there are moments and there are movements, and we need to make sure that this is not a moment. There are a lot of networks and organizations that have been behind pulling all this together, and they're still there. So making sure that this doesn't revert back to "I recycle" is going to be the thing that we need to do. This can't be about individual action. It needs to be about system change and a totally different cultural status quo.

NO: I agree wholeheartedly.