Why don't Americans care about chemicals?

We need chemicals for daily life, but seem to feel 'apocalypse fatigue' around their dangers

Chris / Flickr

For the past four years, researchers at Chapman University in Orange, CA have surveyed Americans to determine what we fear most. Polled at random, people were asked to rate their level of fear of about 80 different topics, including crime, terrorism, the government, environmental pollution, and personal fears.

For the first time in 2017, environmental fears ranked with Americans' top 10 greatest fears: “pollution of oceans, rivers, and lakes,” “pollution of drinking water,” “global warming/climate change,” and “air pollution” all jumped into the top 10. They bumped perennial fears, about the economy, government, and terrorism, further down the list.

Increased concern about environmental pollution should not necessarily surprise us. In 2017, the Trump administration supported a market shift in US environmental policy and enforcement. That change has brought new attention to an old fact: we’ve created a whopping number and volume of chemicals over the years for use in industry and public health, somewhere around 140,000 formulations since 1950. Many of these chemicals can leach into the environment and into living creatures.

Although relatively few chemical pollutants are thought to be harmful to human health, only a paltry 2 percent or so of extant chemicals have been well-vetted for safety and toxicity by the US Environmental Protection Agency. We're learning more every day about these significant levels of ambient contaminant exposure in the US, bringing this sort of pollution more into public awareness.

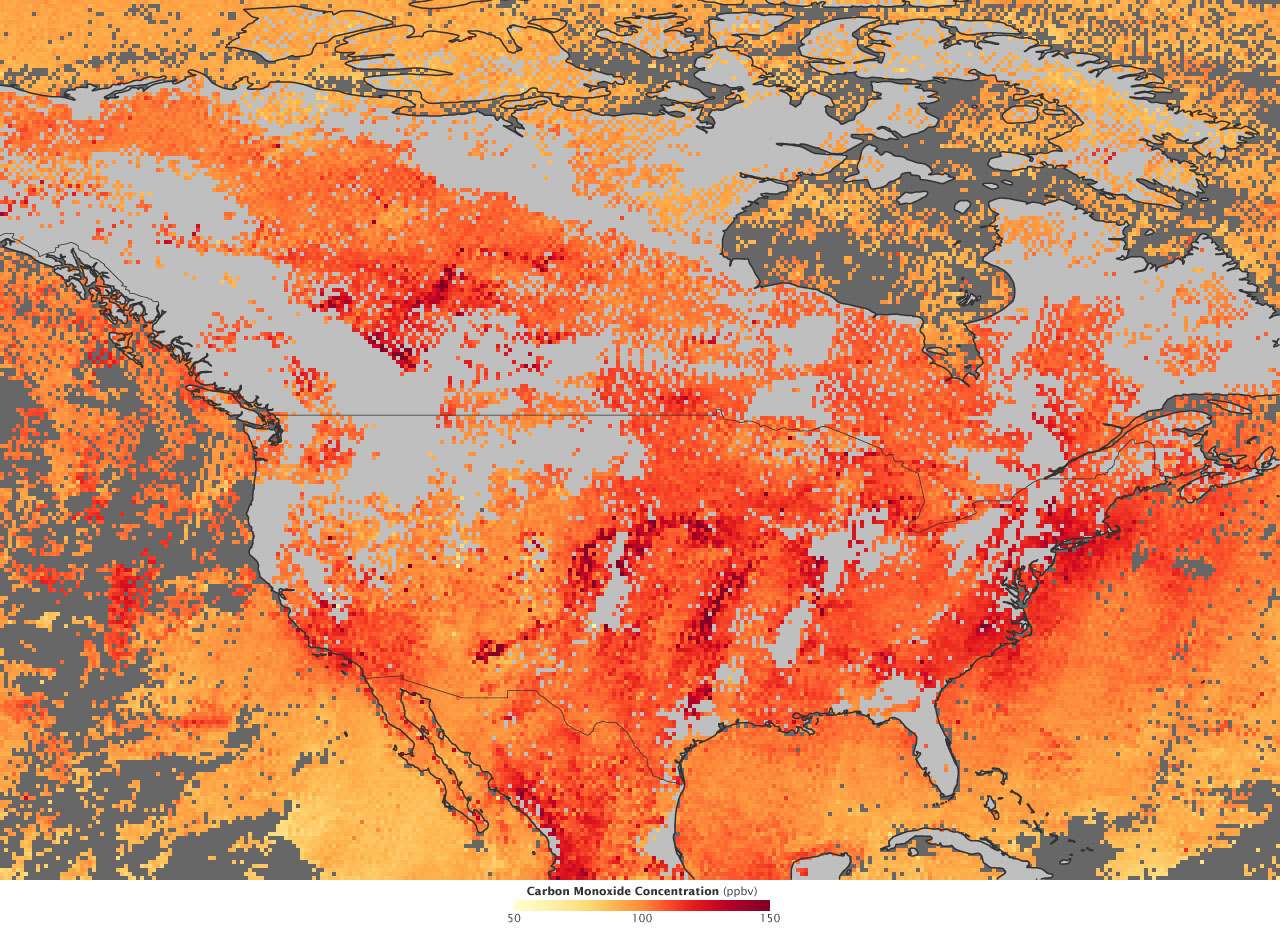

Carbon monoxide in the US

Though comparatively few in number, harmful synthetic chemicals can wreak havoc on public health around the globe. In 2015, an estimated 16 percent of all premature global deaths were caused by pollution and pollution-related disease, more than 15 times the number caused by war and all forms of violence combined. Ninety-two percent of these pollution-related deaths were in low- or middle-income countries, mostly related to air pollution. In the US, roughly 200,000 premature deaths each year are attributed to air pollution from combustion processes, like ground transportation and fossil fuel power.

Compelling evidence also suggests these chemicals impair the immune system and vaccine effectiveness, child brain development and learning ability, human fertility, weight loss, social behavior, cancer, and a slew of other diseases. You don't need to work in a chemical plant for high exposure: we encounter pollutants in everyday activities, in concentrations that have been demonstrated to be impactful, in the here and now of normal life.

A chemical Catch-22

Looking at these figures and facts, something seems amiss. We rely on power plants and manmade chemicals every day, and they are supposed to better our lives, not cut them short. But here we are, caught in a chemical Catch-22: some of these same chemicals we count on – for energy, medicine, food, technology – can harm us and wildlife when they're let loose, as they inevitably are.

Why do we allow chemicals to slip into our lives and bodies? Because it’s largely legal, at least in the US. Unlike more protective rules in Europe, chemical policy in the US errs away from the precautionary principle, which states that given two courses of action, with incomplete knowledge of the consequences, the more cautious approach should be followed. Under the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and a 2016 update of the law, the burden generally falls on scientists to prove chemicals are harmful, to humans or the environment, before regulators intervene; chemicals are assumed safe until proven guilty.

Ken Douglas / Flickr

The dangers of new chemicals are evaluated according to new and existing rules that critics argue have been substantially weakened by the current administration; proponents argue that new emphasis on speedy chemical approval is good for business and still protective of public health, collecting increased fees from manufacturers to defray TSCA implementation costs. Regardless of individual TSCA opinion, the overall jump-first, think-later approach can be costly – in terms of health, lives, and money – yet the public has yet to demand significant revisions to chemical regulations in the US.

Working in contaminant research, I wrestle with our relationship to chemicals every day. I recognize how important modern chemicals are for public health and safety. Yet at the same time, I see environmental contaminants behind cancer in my loved ones, in snake-oil ads for new miracle products, or when a friend tells me over the phone that she just can’t conceive. On most days, these realities motivate me to keep working, to find ways to measure and understand pollutants – to learn more so that we might better understand or regulate the chemical cocktail all around us.

But on bad days, I feel confused and frustrated and a little alone. Why is it so difficult for us to care about toxicants all around us, despite such dire consequences for ourselves and the people we love?

'Apocalypse fatigue'

Over the last two decades, psychologists have hypothesized that we respond – or don't – to faceless threats like climate change according to the way those threats are framed in contrast to the status quo. Economists, policy experts, and journalists have expounded on an outcome of this type of thinking, suggesting several terms to describe the phenomena: “threat fatigue," “resistance fatigue,” and “apocalypse fatigue” all roughly mean the same thing –that we tire out from constant threats that challenge our modus operandi and thus don't take any of them seriously enough.

Per Espen Stoknes, a Norwegian psychologist and economist, suggests five mental defenses that stifle public engagement with the climate change: distance, doom, dissonance, denial, and identity. In a nutshell, we often see climate change as apocalyptic but far off, at odds with our accepted lifestyles. So we often deny our role in it or refuse to act, unwilling to confront what it means for our habits and identity.

If you listen to Stoknes' TED talk on the subject, you can substitute “synthetic chemical risk” almost everywhere he discusses climate change. Both are faceless, seem distant, and ostensibly require action outside of our routines: the same psychological and cultural barriers seem to influence how we see pollutants, and to neuter public concern and action. We may know that chemicals are all around us and may affect our health, but it seems like a minor threat, or one that is out of our hands, a danger beyond the actionable capabilities of any one person. These paralyzing assumptions mean chemicals keep getting introduced with little vetting. And people keep falling ill, sometimes fatally, as research struggles to catch up to how chemicals contribute to disease.

Where does this leave us?

The same solutions that encourage action on climate change may also help raise appropriate concern for chemical exposure. Stoknes suggests five approaches, readily transferable to our dilemma: discussing the issue in ways that make the threat personal; framing the issue in concrete ways – jobs, safety, etc – rather than global doomsday tidings; providing simple actions to make a difference; and finding better stories to break through denial or polarization.

Several organizations and many scientists are working on these goals already. Last winter, the journal PLOS released a special collection, “Challenges in Environmental Health: Closing the Gap between Evidence and Regulations,” in which a cast of experts filled the collection with short, easily understandable perspectives and essays.

The collection touched on the shortcomings of current law, what goes into our food, how toxicants affect children, how we can better protect drinking water, and a recent policy decision not to ban a pesticide. Each piece framed contaminant topics in terms of public health, policy, and solutions, going a step beyond sterile observations of most peer-reviewed articles. While the opinions were mostly of a kind, the expansive, interdisciplinary approach was both refreshing and riveting. Looking ahead, such holistic thinking is likely what's required from everyone.

What's in the food?

Jens Hembach / Flickr

Chemical regulation still faces resistance in the US. Even the collection's editor, Linda Birnbaum, the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health and Safety, was demonized by politicians who accused her of lobbying in her introduction. It can feel disheartening, but other, similarly accomplished scientists have started to speak out, too, including Joseph Allen from Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Richard Corsi from University of Texas. There are even new smartphone apps to better gauge individual exposure potential.

These figures set an example for how to discuss chemicals conversationally and to suggest consumer solutions with policy ones: we should try to tell better and more accurate stories, and to have an open mind. The results of the Chapman University study, indicating Americans today worry about environmental pollution, underscores the increasing effectiveness of more and better storytelling about pollution.

I personally have witnessed a sea change in my own loved ones over the past few years; my mom and dad, far from environmentalists, now try to buy organic foods and tell others about chemical safety. Engaging in these sorts of honest conversations about chemical pollution benefits us all, and will hopefully create fair solutions that support public health, the environment, and the economy.

Peer Commentary

Feedback and follow-up from other members of our community

Laura Mast

Environmental Engineering

Georgia Institute of Technology

In my lab, we work on treating personal care products (shampoo, soap, that kind of thing) and pharmaceuticals in drinking water. We now know that our drinking water contains low (VERY low) doses of caffeine and other common chemicals we put in our bodies: estrogen, from birth control medication; metformin, which is a diabetes drug; lipitor, a cholesterol drug; and carbamazepine, an epilepsy drug, to name a few. All these chemicals mingle around in our waterways and water treatment plants, in concentrations so low that it’s cost prohibitive to treat. Retrofitting our treatment plants to be able to destroy these drugs would also be terribly expensive.

And, maybe not necessary; maybe a chronic low dose of caffeine (or estrogen) isn’t so bad for you.

The sheer numbers of chemicals we release into our environment is what makes this concerning for me, as an environmental chemist. What are those drugs doing in there? How are they reacting??

I’d love to hear more about your drinking water work at some point.

I have no idea about the costs involved behind drinking water removal techniques and how it balances with human risk assessments. Are you doing anything related to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) removal from drinking water?

And yes, the sheer volume is crazy! Figures cited in the article I believe are inventoried chemicals produced, probably not indicative of degradation products or recombinant structures.

While I can’t say drinking water or surface water contaminant levels are exceeding no-observed-adverse-effect (NOAEL) levels, I do have to disagree with you on one point: chronic low doses of emerging (or even legacy) contaminants can be deleterious to aquatic populations of autotrophs, fish, and invertebrates, based on some compelling peer-reviewed research. I don’t think there’s a true understanding regarding what chronic low doses do to humans though, but considering PFAS issues in drinking water and our reliance on functioning aquatic food webs, I’d say we do have a horse in the race in terms of caring about chronic, low-dose impacts.

Check out some of my past articles on Massive here and the references therein, particularly Karen Kidd’s work in the ELA, some of the mixture toxicity work done by Pedro Echeveste’s group, or some of the wild variation between PFOA and PFOS drinking water safety levels espoused by different states. Hope to chat further about your drinking water work!

Natalie Parletta

Psychology, Nutrition

University of South Australia

In my focus on developmental disorders (and nutrition) I was particularly concerned by this 2006 Lancet article on developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. -What has changed since then? Apocalypse fatigue is an enlightening concept.