Mating plugs and other weird butterfly sex habits

Male butterflies want monogamy. Females, not so much.

Charles J Sharp on Wikimedia Commons

When it comes to butterflies, most people are drawn to their exquisite, colorful wings. But Ana Paula dos Santos de Carvalho is busy looking at their genitalia and reproductive organs—specifically their large, elaborate mating plugs.

“The wings are mesmerizing, but to me, these plugs can be very mesmerizing, too,” says Carvalho, an entomology PhD candidate in the Kawahara Lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Originally mistaken as egg catapults in the early 1900s, these external mating plugs, also known as sphragis, seal off a female’s genitalia to prevent future insemination from other males. Butterfly mating plugs come in all shapes and sizes—some are curled like shells, some are hooked, others are pronged like a pitchfork that can be used to jab other males. “In some species, part of the plug is like a chastity belt that goes around the abdomen of the female,” says Carvalho. “So it really holds that thing in place.”

Found in approximately 1 percent of butterfly species, males wield their ornate mating plugs to enforce female monogamy and ensure paternity of the offspring. However, females try to thwart this strategy, attempting to increase the genetic diversity of progeny by mating with multiple males.

“It’s an ongoing battle of males and females,” Carvalho says. And butterfly sex can be more violent than you’d might expect.

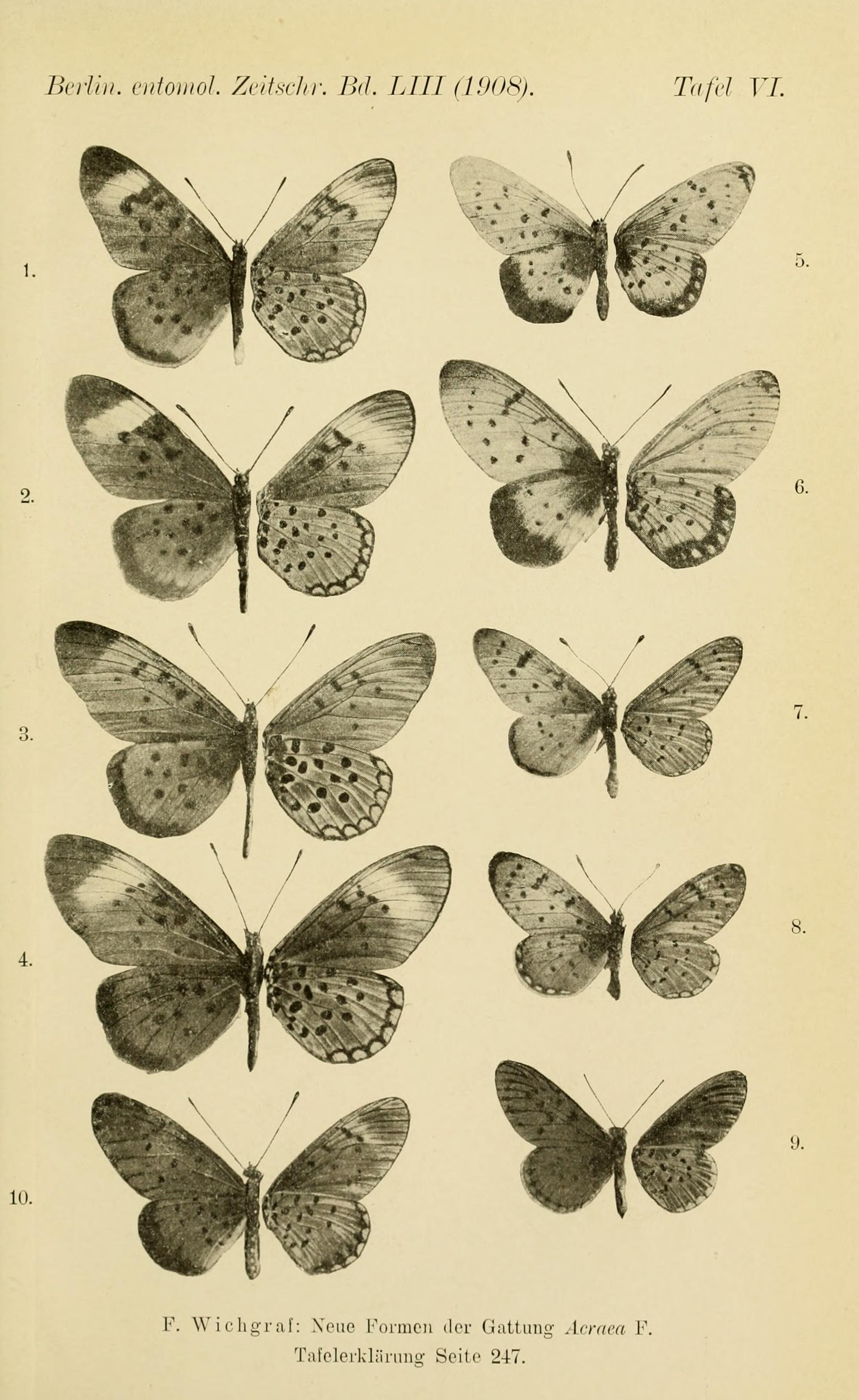

Some Acraea butterflies related to the ones used in the study

Wichgraf on Wikimedia Commons

During her master’s research at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, she was conducting a butterfly diversity survey in the grasslands of Southern Brazil, when she came across an unusual female specimen of the endemic species, Euryades corethrus, common name Campoleta. As the butterfly folded its tan, mottled wings, she was surprised to see two large spikes sticking out from the female’s abdomen.

“They were almost as long as the size of the abdomen,” she says. “I was like, ‘OK, this is really strange.’”

It was the first time she observed a butterfly mating plug. Her advisor explained that the two projections were flaps of a wing-shaped plug distinct to Campoleta. Now studying butterflies in museum collections, Carvalho has observed all kinds of the extreme shapes and architectures. She’s even stumbled upon females with multiple plugs attached in odd positions.

Get a room!

Jeevan Jose on Wikimedia Commons.

Male butterflies invest a lot of energy into creating mating plugs. The complex, waxy structures are shaped in a mold inside the tracts of the male’s reproductive system. Once made, they insert the plug into a female’s copulatory opening. These plugs can be permanent. In other animals that only have one opening for mating and birthing offspring, a plug has to eventually dissolve or be removed for the female to lay young, says Carvalho. Since the female butterfly reproductive system has separate openings for both, a plug can remain and effectively prohibit females from having other mates.

“That is the ultimate goal,” says Carvalho. “If one of the major drivers of evolution is to produce offspring in future generations, then you have a great strategy for males.”

But females benefit from having multiple mating partners. More mates means an increased chance of receiving higher-quality sperm and a boost in genetic diversity of offspring, she says. So females have developed various kinds of countermeasures. She’s found females in some species with a hardened, smooth plate around the exposed genitalia—a feature that might make it challenging for the male to attach the plug, says Carvalho. In others, she’s observed genitalia tucked inside a large cave-like structure that could be difficult for a male to plug completely. “Females have evolved these adaptations of genitalia, where either males are going to have to allocate a lot of resources to plug them or they’re just going to have to give up,” she says.

This sexual conflict is seen throughout the animal kingdom. You can find mating plugs in snakes, squirrels, kangaroos, bees, scorpions, and various other mammals and arthropods. The vast diversity of butterfly mating plugs is possible evidence that sexual conflict might drive the creation of new species.

In a recent study published in Systematic Biology, Carvalho poured over hundreds of brush-footed butterfly specimens in various museum collections, including Florida Museum, the Smithsonian, and collections in California and Canada. In the butterfly tribe Acraeini, a group of about 300 species, Carvalho investigated if diversification rates were tied to the trait.

“Males and females are both in this arms race, evolving these new adaptations that could result in new butterfly species appearing.” Past studies and research groups have supported the link between high rates of speciation and plugs. However, after multiple analyses of the data, she found no difference in speciation between butterfly groups with plugs and those without.

“Maybe we need to rethink the way sexual conflict could be associated with diversity,” she says. “Maybe it’s more complex than that.”

Carvalho and the Kawahara Lab say other factors could be increasing species diversity, such as habitat and species distribution. Carvalho is looking to investigate mating plugs further and expand her work into sexual behavior of other insects. The sex lives of these organisms are both fascinating and surprising, she says.

“When I start talking about their sexual behavior, people are like, ‘Oh, I thought that butterflies were chill,” Carvalho says. “Oh, you don’t know a thing.”