Brain banks are key to understanding COVID's mysterious symptoms, but only if people are willing to donate

Some COVID-19 patients experience dizziness, loss of smell and even seizures, but we need brain donations from patients and healthy controls to understand why.

Anna Svets / Pexels

After 7 months and counting, we've all had first-hand experience with the stress and uncertainty that have hitched a ride with the COVID-19 pandemic.

This situation is pushing our mental health to its limits. Some patients have been reporting strange neurological symptoms that suggest that the virus might be able to hit the human brain directly. If we’ve learned anything from similar viruses in the past, it’s that the effects of COVID-19 on the human brain may last for months or years after the pandemic is over.

This is precisely why donations to brain banks are vitally important.

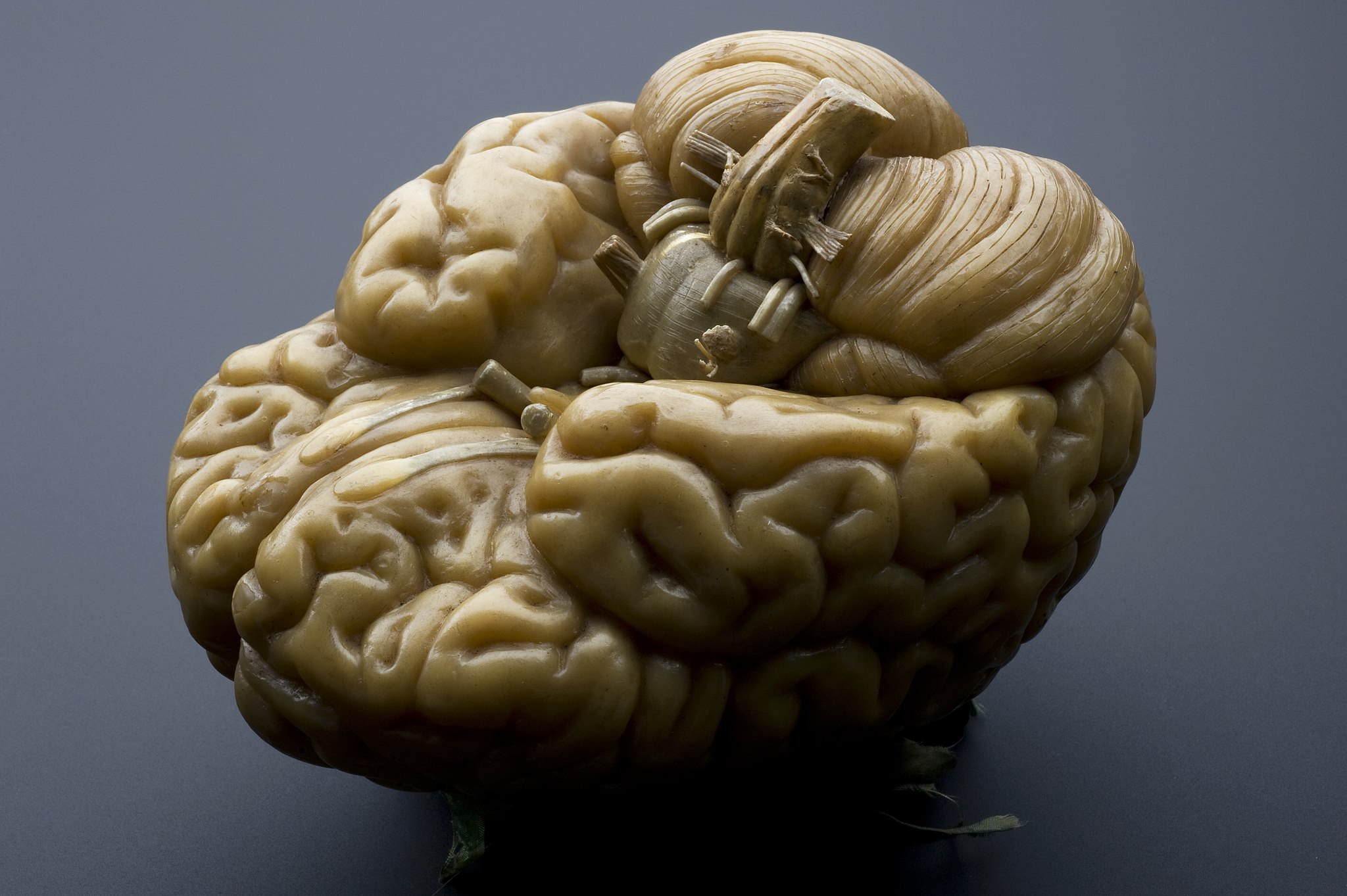

The method for preserving brains was created in the 1600s, and curious physicians and anatomists have been collecting brains ever since. But the systematic banking of brain tissue that exists today began in the early 20th century, arising from a need to study mysterious brain diseases. Today, there are brain banks throughout the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia that each focus on collecting and characterizing samples from specific brain disorders, and providing crucial resources to the research community. Although the details differ between platforms, people can agree to have their brains donated to a brain bank, or their next of kin may be approached by a brain bank team about the possibility of donation after they’ve died. Whether they’ve been diagnosed with an illness or not, each brain donation is meticulously categorized and preserved so that they can continue to be studied, sometimes decades later.

After the SARS pandemic in 2003, researchers used brain donations to discover that the virus could infect brain cells. This could explain why some SARS patients had symptoms like dizziness, confusion and anosmia (loss of the ability to smell). Curiously, reports have started to come out that COVID-19 can cause similar brain-related symptoms in some patients; the most common are headache, anosmia and brain fog, but COVID-19 can also cause seizures, strokes, or comas. There’s even some evidence that these symptoms are related to changes in brain structure, but without donated tissues it’s almost impossible to tell how the virus gets into the brain, or if it infects brain cells at all. It's possible that the virus infiltrates individual brain cells, causing them to malfunction, but the troubling symptoms that some patients experience could also be a side effect of the fever and inflammation that COVID-19 inflicts on the body as a whole. This means that for doctors struggling to find the right treatments and scientists looking for breakthroughs, brain banks might hold the answer.

Naguib Mechawar, director of the Douglas Bell Canada Brain Bank (DBCBB) in Montreal, says that to truly understand COVID-19, brain banks are "more than useful, they’re essential." Whether the virus works through direct contact with brain cells, or through inflammation of the blood vessels in the brain, he adds that "access to human brain samples is required to understand the mechanisms underlying these symptoms. Models remain important, but there’s nothing like patient samples to understand this human illness."

Today, there are brain banks throughout the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia that each focus on collecting and characterizing samples from specific brain disorders, and providing crucial resources to the research community.

Wikimedia

For the virus to actively attack brain cells, it would have to get through the blood-brain barrier — the tight network of cells that plays bodyguard between the brain and the body — first. It turns out that some brain cells express the ACE2 protein that SARS-CoV-2 binds to in the respiratory tract, so it’s possible that they’d be vulnerable to such an attack. Plus, in the lab, the virus seems capable of infecting brain organoids — three dimensional cell cultures that are used to model brain biology — but we can't know if it holds true in humans unless we have access to human brains. Luckily, scientists have started to look at autopsied COVID-19 brains, and in one case, they’ve found bits of the virus inside some brain cells. Once inside, it's possible that the virus can reproduce and spread; but as Serena Spudich, a neurologist who wrote a review about these cases, said to the Guardian “It’s really hard to make firm conclusions based on one or two autopsies.”

Brain banks offer the solution to this problem. By collecting samples from people who were infected with the virus while they were alive, whether they had neurological symptoms or not, and from people who died from other causes, brain banks will be the steady, stable resource for COVID-19 brain research that they have been for other brain-related diseases. Banked brain samples have helped researchers understand how brain-specific immune cells react in Alzheimer’s disease, and how a specific group of cells could be a target for schizophrenia treatment. By accessing medical records, interviewing family members, and carefully examining tissues, brain banks are uniquely able to capture information about an illness before and after it has taken hold of a patient.

In 2000, brain bank scientists from Germany, Austria, and the US, banded together to understand how multiple sclerosis (MS) develops. One of the biggest challenges in treating MS is that the disease can present itself differently in different patients; according to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, "no two people have the exact same symptoms, and each person's symptoms can change or fluctuate over time."

Together, the team led by Claudia Lucchinetti collected more than 80 patient brain samples, and although they found MS-related brain cell damage in all their samples, they noticed some interesting patterns. By carefully examining the distribution, size, and protein composition of the damaged cells, they found four distinct patterns that gave them clues about how the disease developed in each patient. These patterns could help doctors to diagnose and treat MS in living patients, and they would not have been found without donations to brain banks.

Brain banks will become even more important in the fight against COVID-19 as we understand more about the behavior of the virus and the symptoms of COVID-19 patients. In addition to neurological symptoms experienced during their sickness, a troubling number of people have reported continued confusion and memory difficulties, called "brain fog", in the months after they've recovered.

Fortunately, efforts are underway to begin collecting COVID-19 brains, and Mechawar says "We [at the DBCBB] have been working actively to set up some mechanisms to collect such brains, but it has been difficult, namely because autopsy rooms have been shut down during the pandemic. But I’m glad to say that we’ve managed to establish new partnerships and purchase new equipment to facilitate things and that we will soon be able to initiate the collection process."

Although it’s not clear whether brain banks will help find a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, they will continue to be an important pillar of COVID-19 research as the pandemic dies down. If they receive enough donations, that is.

Peer Commentary

Feedback and follow-up from other members of our community

Meredith Schmehl

Neurobiology

Duke University

This was a fascinating read, Kathryn! I’m wondering if you have thoughts about “banks” for other organs that can be affected by COVID-19 or other diseases, such as the lungs. It seems that similar organ banks might accelerate research on how these diseases affect the body as a whole, but there may be ethical and values-based difficulties with getting donors for such comprehensive research.

Marnie Willman

Virology

University of Manitoba Bannatyne, National Microbiology Laboratory

Great article, Kathryn! Brain banks are something few consider when it comes to Covid, because it’s primarily a respiratory virus. That said, it’s important to have a variety of different tissue samples so we can see how the virus spreads throughout the body, and where it is capable of causing successful infections. Particularly if the brain does have ACE2 receptors that SARS-CoV2 looks for, then that makes the brain this much more interesting. Hopefully this will begin to show people how vital these banks are, and why it’s important to donate to them!

Anna Wernick

Neuroscience

University College London

A great read, Kathryn! Whilst many consider the option of organ donation after their death, few seem to consider brain bank donation in order to advance scientific research. Articles like this will hopefully not only promote the importance of brain donation for research purposes but also highlight the neurological symptoms of COVID-19. As a neuroscientist myself, the neurological consequences of COVID-19 are what scare me the most about the virus - especially the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, reported in The Lancet in October: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(20)30305-7/fulltext