When the Bering Sea freezes over, it sings. As wind and current shift, the ice crackles and moans, piping through the polar night.

Among these moving giants rises St. Lawrence Island. Closer to Russia than the United States, its granite cliffs uplift rock as old as the Palezoic era, when an explosion of life spilled over the Earth. Waves have since cut away lake-dotted plains, and its headlands, once hugged by ice for much of the year, are rugged, with spare, bouldered beaches.

When Delbert Pungowiyi was born in 1959, the island had no electricity or cars. People were just beginning to use heaters. His family and their Yupik community relied on dog teams to travel, and ate what the land and sea gave them. When he was six, Pungowiyi’s father passed away in a hunting accident. “We had to grow up real fast to contribute,” he says. The winters were long and hard, and Pungowiyi’s family worried about running out of food. But the light always crept back. The sea would unlock, fast ice clinging to the shore. Then one day, the birds would come.

“It was a spectacle,” Pungowiyi says. “They would literally blacken the skies, swarms and swarms, circling.” A critical nesting ground, St. Lawrence Island draws millions of seabirds — puffins and auklets and murres — in migratory flocks, traveling vast distances to arrive precisely with the last of the ice. Pungowiyi could hear their calls from his bed, and ventured out to the cliffs with a homemade slingshot to harvest what his family needed. He was a good shot, but “a lot of times, I’d just lay there and look up at the sky, and watch the birds go around and around.” He marveled how, despite their careening speeds, the birds never seemed to collide. The air would still to the whoosh and thump of wings.

But the Bering Sea, the only marine gateway between the icy Arctic and the Pacific Ocean, is warming. More and more of its multi-year ice has melted. Normally, more than 193,000 square miles of ice would form across the Bering Strait each winter. In 2018, there was almost none, a development that scientists originally didn’t forecast until the end of the century. “That’s about two Texas’s worth of ice that is missing,” wrote Walter Meier, a scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center. The sea’s winter ice extent in 2018 and 2019 was the lowest it has been for 5,500 years.

Ice is the keystone of this ecosystem: When it melts, it releases fresh water and nutrients, sustaining algae and phytoplankton blooms, which in turn support some of the biggest fisheries on the planet. When floes form, they shed briny, cold water, forming a frigid ocean curtain that supported Arctic species and kept southern ones, like pollock and cod, out of the Arctic Ocean. This cold pool has been shrinking. In 2018, researchers were shocked when it vanished almost entirely.

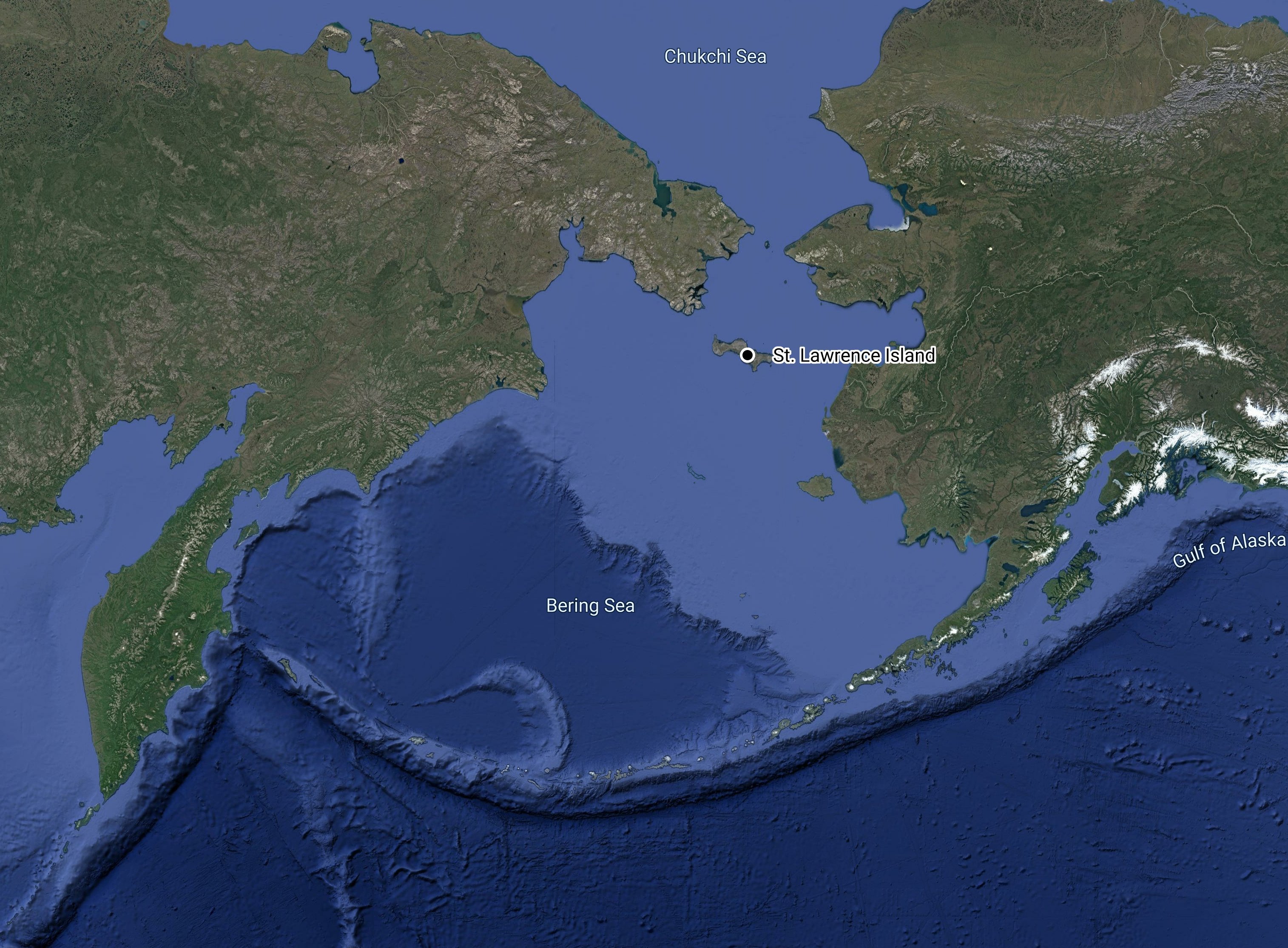

St. Lawrence Island, between the Russian far east and Alaska in the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea is now trapped in a feedback loop: Open water absorbs more heat from the sun, warming the dark waters, and making it harder for ice to form the next year. Summer sea-bottom temperatures have increased by more than 12 degrees in less than a decade, impacting everything from the patterns of currents to nutrient availability to what fish thrive where. Even the salinity of the water itself is changing as older ice melts. Before, Pungowiyi says, “Young ice — we call it sikuliaq — was almost like a water bed, every step bends.” Hunters trusted it when they ventured out to fish or crab. But thinner, newer ice, he says, “is brittle, and breaks up.”

This loss is echoing up the food chain. The Alaska snow crab population has crashed. Ice seal carcasses have increased five-fold. Emaciated gray whales are stranding themselves. And in 2021, for the fifth consecutive summer, communities all over western Alaska reported dead seabirds washing ashore. Residents from small towns along the Bering Sea have been mailing corpses to biologists in boxes, hoping the scientists can figure out what’s killing them.

At times on St. Lawrence Island, Pungowiyi says, “The beaches have been literally littered with carcasses.” He mourns over the bodies of crested auklets, slick, black diving birds with a splash of feathers like bangs. When they wash up, their keels curve out of gaunt chests. “Since the cold curtain lifted, the impact has been accelerating,” Pungowiyi says. “It literally sends chills down my spine to see this in my lifetime.” These changes are altering peoples’ relationship with the food they depend on. In town, the constant murmur and chatter from the cliffs is eerily quiet.

“As a young man growing up, I thought this will always be. And now I see that what I thought is really not…” he trails off. “It’s heart-wrenching.”

A crested auklet colony can be smelled before it's seen: The chunky, raucous birds give off the smell of tangerines from a hundred yards. In the thrill of spring, males will puff up their distinctive crest. If a potential partner is interested, she’ll bury her beak in his neck feathers, where the citrus scent is strongest. Then the pair twist their necks together and rub, cackling. Onlookers egg them on in a scrum, pressed close as if on a crowded dance floor.

Although seabirds of many species gravitate to St. Lawrence, Alexis Will, a biologist at the Institute of Arctic Biology, says the extent of the island’s crested and least auklet colonies make it unique. They are so large that she needs an ATV to survey them. “You’re driving along and it’s just these clouds of birds,” she says. Bumping over the tundra, the nesting cliffs dropping off to the ocean look like the edge of the world. The island is one of only about 100 known crested auklet nesting sites. “You just see these swirls of birds for kilometers. They go on forever.” Her voice breaks. “It’s hard to see how amazing it is — and then to see that start to fall apart.”

A crested auklet

Alexis Will

The lives of seabirds are perilous, and occasional die-offs are normal. But recent events are different: They’re happening more frequently, lasting longer, impacting more species, and covering larger geographic areas.

In 2015, as many as a million common murres — a highly adaptive species — died in the Gulf of Alaska after an unusual marine heat wave. That catastrophic event was soon followed by many others, with die offs happening year after year around the Bering Sea. This September alone, 650 dead birds — shearwaters and common murres and horned puffins — were reported around St. Lawrence Island; Will says that since most birds die unobserved at sea, that’s likely a large underestimate of the true mortality.

There isn’t a single, easily explainable cause. Rather, the likely culprit, climate change, is impacting each location and species differently. “There are lots of ways to die off,” Will says.

Seabirds like the crested auklet eat small zooplankton called copepods, tiny shrimp-like creatures. Kathy Kuletz, a seabird biologist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, explains that as the Bering Sea warms, large, lipid-rich copepods have declined. While smaller copepods are proving more resilient, they provide less energy for the fish and birds who rely on them. The collapse of the Bering Sea’s cold pool may have also increased competition for prey, as predatory fish like pollock move north. “To feed a chick, a bird might have to catch three pollock, instead of one arctic cod, which is richer in lipids,” Kuletz says, causing chicks to mature slower, or fledge late, with fewer surviving to breed. “Things are changing, probably faster than some species of birds can respond.”

Starting in 2017, Will found that copepods nearly disappeared from both auklet species’ diets. This summer, when a friend of Pungowiyi’s went to harvest birds, he was devastated by their condition: The stomachs of the emaciated birds weren’t the usual color — they clearly weren’t eating their normal prey. Punguk Shoogukwruk, a St. Lawrence resident, has been collaborating with Will for the last three years, catching and measuring birds. He has noticed chicks dying of hunger, as well as starving fledglings abandoning their nests prematurely. “To be going around checking nests and seeing one dead chick after another is pretty much the worst thing,” Will says. Neither auklet species produced any surviving chicks in 2018 or 2019; the pandemic has limited her field research since.

Scientists have found that shifting wind patterns have broken down the normal transport of sea ice and currents, impacting how nutrients are dispersed through the ocean, and possibly changing where auklets can find their staple prey. Strong, warm southerly winds have been forcing the remaining ice north, redistributing zooplankton — and everything that depends on them.

It’s difficult to track the rapid changes occurring in this critical habitat, much less predict their consequences. The thick-billed murre, for example, which also nests on St. Lawrence Island, mostly eats small fish that live near the sea bottom. These fish populations appear stable, for now. But even though the murres seem to have enough food, they died in droves around St. Lawrence in 2018. The number of returning thick-billed murres fell the following summer by 25 percent. Scientists wonder whether their prey moved to unusual or harder to access locations. Worsening toxic algae blooms and avian disease could also be contributing factors, but so far, research has been inconclusive. “The Bering Sea is in such a state of flux right now that there’s not necessarily any established pattern,” Will says. “It’s all broken down — the system is in a state of freefall.”

A least auklet

Alexis Will

Will has been studying seabirds that nest on St. Lawrence since 2016. By measuring a stress hormone called corticosterone, she recently found that all five of the species she examined on the island are experiencing high nutritional stress. Each dives to a different depth, and targets different prey, but starvation is their common suspected enemy. “The seabirds we’ve been tracking encompass pretty much the range of how you can make a living in a marine environment,” Will says. “Basically, none of the birds are winning.”

Some seabirds live for a long time. Kittiwakes, for example, can live to 30 years old. But crested auklets have flash-in-the-pan lives; they sport their tangerine smiles for less than a decade, intensifying pressure on the efforts to understand what is going wrong. Least auklets live for even shorter periods. After two years with a complete failure to breed, their population may already be slipping away. On St. Lawrence Island, if this trend continues “we have about a decade for least auklets, maybe less,” Will says. “And there’s really nothing we can do — it’s climate change.”

In 1983, Pungowiyi was sitting in his grandfather’s house, the home he inherited and lives in today. “Things were pretty normal back then,” he says. They were on the couch watching TV when his grandfather turned to him. “Remember what I tell you,” he said in Yupik. “I will not be here, but you will witness the loss of ice.” Although Pungowiyi’s grandfather didn’t use scientific terms like “climate change” or “unusual mortality events,” he knew through close observation that the weather had begun to shift.

By the 1990s, Indigenous reports that the Arctic was changing made it into a few academic studies. It took another decade for the wider scientific community to pay attention. “Our ancestors believed all oceans were connected,” Pungowiyi says. The Bering Sea plays a crucial role in the marine conveyor belt that regulates the world’s oceans. Changes here can possibly interfere with the jet stream, weakening the polar vortex and affecting everything from drought in the American West to record-breaking rainfall in Europe. “I fear if the Bering Sea ecosystem collapses, it will have a domino effect,” he says.

When Pungowiyi learned to hunt from his grandfather, the island saw nine months of solid winter, with freeze up starting in October and break up extending into June. He learned to predict the weather by ocean ripples, and the formation of drifting snow. The long cold thickened the ice, making it possible to hunt and travel. Village monitors on St. Lawrence Island began recording the daily ice extent in 2000, when gleaming, multi-year bergs still blued the islands’ beaches. Now, winter lasts for three months, Pungowiyi says, four “if we’re lucky.” When it snows, he hears kids saying that it’s winter, and explains to them that the season, uksuq, only begins when “the whole of the sea is locked up, and there’s no more open water. That’s winter.” Some years now, uksuq doesn’t come at all.

Punguk Shoogukwruk performing field research

Alexis Will

In the old patterns of life, animal behavior was once so habitual that the Yupik word for July is alpaarusvik, literally “time when the murres leave.” But in 2007, for the first time in the elders’ memory, flying cormorants arrived in mid-winter. The seals come early, and the whales late. “We’re seeing big shifts in availability and abundance of species,” says Lisa Sheffield Guy, a biologist and the project manager at the Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S. Hunting requires an intricate understanding of the weather, but travel on thin ice is perilous, and recently, warm, dangerous winds rise out of nowhere, sweeping ice and anyone on it offshore. “One thing we do still rely on is clouds,” Pungowiyi says. “They always tell the truth.” For everything else, the changes are so fast, and so fundamental, they are outstripping traditional knowledge.

These shifts are driving food insecurity on the island. “People depend on the yearly harvest of eggs, and lately there have been less and less,” Shoogukwruk says. In addition to hunting birds, residents collect eggs during the brief nesting window, and then freeze them. But as access to these kinds of food sources change, many are having to increasingly rely on imported food. The cost of shipping goods out to St. Lawrence is high, and grocery prices are steep; a half-gallon of milk costs over $10 and a box of cereal can cost $8. Pungowiyi is among the many residents who visit the food bank in town, but it struggles to keep up with demand.

Pungowiyi has spent the last few years trying everything he can think of to get people to pay attention, including inviting Senator Lisa Murkowski out to the island. Yet scientific and governmental responses have been slow. As the former tribal president, Pungowiyi recently traveled to an Arctic Council meeting, where he was excited to speak to some of the world’s top scientists. He planned a talk, hoping to describe the die-offs he’d witnessed, but “they had us in a tiny little room on the second floor,” during the lunch hour. He decided he was going to find a way to speak to the full gathering, in the big room. In a break for questions, he walked up to one of the microphones, wearing a hat his mother had embroidered with two polar bear heads. “I had made up my mind to speak as quick as I can, until they cut me off,” he says. And then he told the room about his grandfather’s warning, and the island’s birds dying.

Pungowiyi hoped sharing what he’d seen would wake people up, get them to do something. Instead, it became clear no one was grasping the urgency of the crisis. “I feel at the end of my rope,” he says. He was distressed by the recent international climate talks in Glasgow, which he felt failed to recognize either Indigenous voices or the major impact he’s seen on the oceans. “The table they are talking at was our table,” he says. “But they have just pushed us aside.”

Igor Krupnik, an anthropologist and Arctic ethnology curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, has known Pungowiyi for years, and watched him grow more and more desperate. Drama is antithetical to a culture where people had to tolerate each other through long winters, Krupnik says, so Pungowiyi’s outward-facing advocacy is particularly striking. “Delbert is a very strong person, who is now in a moment of hopelessness,” Krupnik says. He, too, seems troubled. “Is this what our life is going to be, without birds, and without ice?”

Kitnik, a beach outside Savoonga

Alexis Will

As I continued reporting, I kept hearing the same story. “Yeah, Delbert called me too,” says Jon Rosales, a climate scientist at St. Lawrence University in New York who has been documenting the impacts of global warming on Native peoples in the Arctic, and whose mother-in-law is from St. Lawrence Island. “You feel helpless, that’s where the despair comes in,” he says. “You hear these stories from the frontlines, and yet the solutions are really global.”

Even if every country meets its current climate targets, there will still be catastrophic amounts of warming. Scientists recently found that if the world continues business-as-usual, likely temperature increases will cause biological and chemical conditions in more than half the ocean to become “new and significantly different.” Not everything will suffer: Without ice, a different kind of plankton will bloom, supporting fish that swim near the ocean surface, and the animals that eat them. But the balance has shifted. Far short of extinction, the island’s old ecology is unraveling. “The biggest realization for me is it’s not done,” says Will. “We’re in this wobbly state, where the system probably won’t ever go back to how it functioned before, but it also hasn’t settled into a new steady state of being.”

Everyone is handling these changes differently. Shoogukwruk says he knows the island’s residents can adapt, because they have before: when the Russians came, when their land was sold to the United States, and when they were forced into living in villages. “We’re still here. And the animals are fighting the same way. It might be hard,” he says, “but if we can’t adapt, then what are we going to be?”

One weekday morning, I reach Pungowiyi while he’s making pancakes for his grandson. He’s tired. “It won’t get any better for our children. Those are the ones I hurt for the most.” In the background, his grandson calls to him. “I wish I could tell those giant [fossil fuel] companies, all the wealth they accumulated will become useless, and their children and grandchildren will suffer. For god’s sake — what are you going to leave behind for them?”

We sit for a moment, and then he says he was “thinking about the environmental lady who wrote about the birds that sang, and are no longer there.” I tell him she also loved the sea. “It’s really on the verge of collapsing. We can’t stop it,” he says. “But it needs to be documented. The world needs to know it is unfolding.”

Anyone who has stood on a shore and watched a bird dive to where they can’t follow knows its dip and disappearance, like a trick of the eye. Seabirds live in the in-between, plunging from the sky into the deep, slipping back and forth between laws of motion. Their future might be liminal, too. “If you cannot save the physical birds, you probably can save a memory of the birds in culture,” Krupnik says. Small salvage, knowing that even as the island’s colonies dwindle, our very longing might preserve a time when the sky here drummed to life with wings.